The new farm laws will make it more difficult for farmers to earn an income, said R.S. Amaresh, a 65-year-old farmer from Renukapura village in Challakere taluk of Chitradurga district. ‘It is very difficult to survive as a farmer. There is no value for our crop. We have given up hope on agriculture. If it continues like this, a day will come when there will be no farmer.’ — People’s Archive of Rural India [PARI], January 27.

Whether you’re a Kashmiri or a kisan (farmer) in India growing sugarcane, wheat, rice, bajra (pearl millet), urad (black gram), toor (pigeon pea), rice, ragi (finger millet), jowar (sorghum), maize, mustard, banana, vegetables… in the fantastical eyes of the current BJP government or the private market, or Ambani or Adani or any extractive and exploitative corporation, your life and livelihood are a disposable commodity. Maximum-for-us-few and nothing for you is the maxim of the day, and those with all of their stinking power and money will deploy every violent tactic in their playbook to keep it that way.

Security forces, road blockades, barbed wires, tear gas, water cannons, police lathis (batons), 10-feet trenches, water and electricity cut offs, that were in PARI’s words, “making it almost impossible for journalists to reach the protesting farmers, punishing a group that has already seen perhaps 200 of its own die, many from hypothermia, in the past two months,” paramilitary forces in full riot-gear with AK-47s, restrictive internet services, surveillance drones, and of course their predictably favorite one: labeling kisans who grow our food as anti-nationals — This is the violence you and me are witness to in the immediate scheme of things. But just like in every other sector, this latest assault by the Indian government and the establishment on the country’s poorest is not new. India’s agrarian crisis was set in motion a few decades ago. These new laws are just the latest pattern in a long chain of atrocious patterns.

On September 27, 2020, the central government of India passed three ag laws without any consultation with the kisans themselves. These laws would give superpowers to corporations and, kisans rightly see these laws as sabotaging an already wobbly support structure that includes the minimum support price (MSP) and the agricultural produce marketing committees (APMCs) — the system of mandis — that assures farmers procurement of their food grains; while at the same time paralyzing “the right to legal recourse of all citizens, undermining Article 32 of the Constitution of India.”

Two months later farmers began gathering on the borders of Delhi and other parts of the country, in the streets and maidans (public spaces) to protest these new laws and make other demands including stability from fluctuating crop prices, “a dignified pension for elderly [women] farmers and farm workers… free treatment at good government hospitals… recognition of women’s labour in agriculture by giving them the status of farmers… strengthening the PDS (public distribution system) for rations,” (according to PARI), reforming APMC instead of gutting it, long overdue land titles for Adivasi (indigenous) farmers, debt waiver, adequate storage facilities of their winter crops, freedom from agents who buy at a lower rate than the MSP because you’re at their mercy and so on and so on.

Like Ojha, many farmers in Bihar have been struggling to get better prices for their crops, especially after the state repealed the Bihar Agriculture Produce Market Act, 1960, in 2006. With that, the agricultural produce market committee (APMC) mandi system was abolished in the state. This points to what farmers in the rest of India might face with three new farm laws that were passed in September 2020. — PARI, February 20.

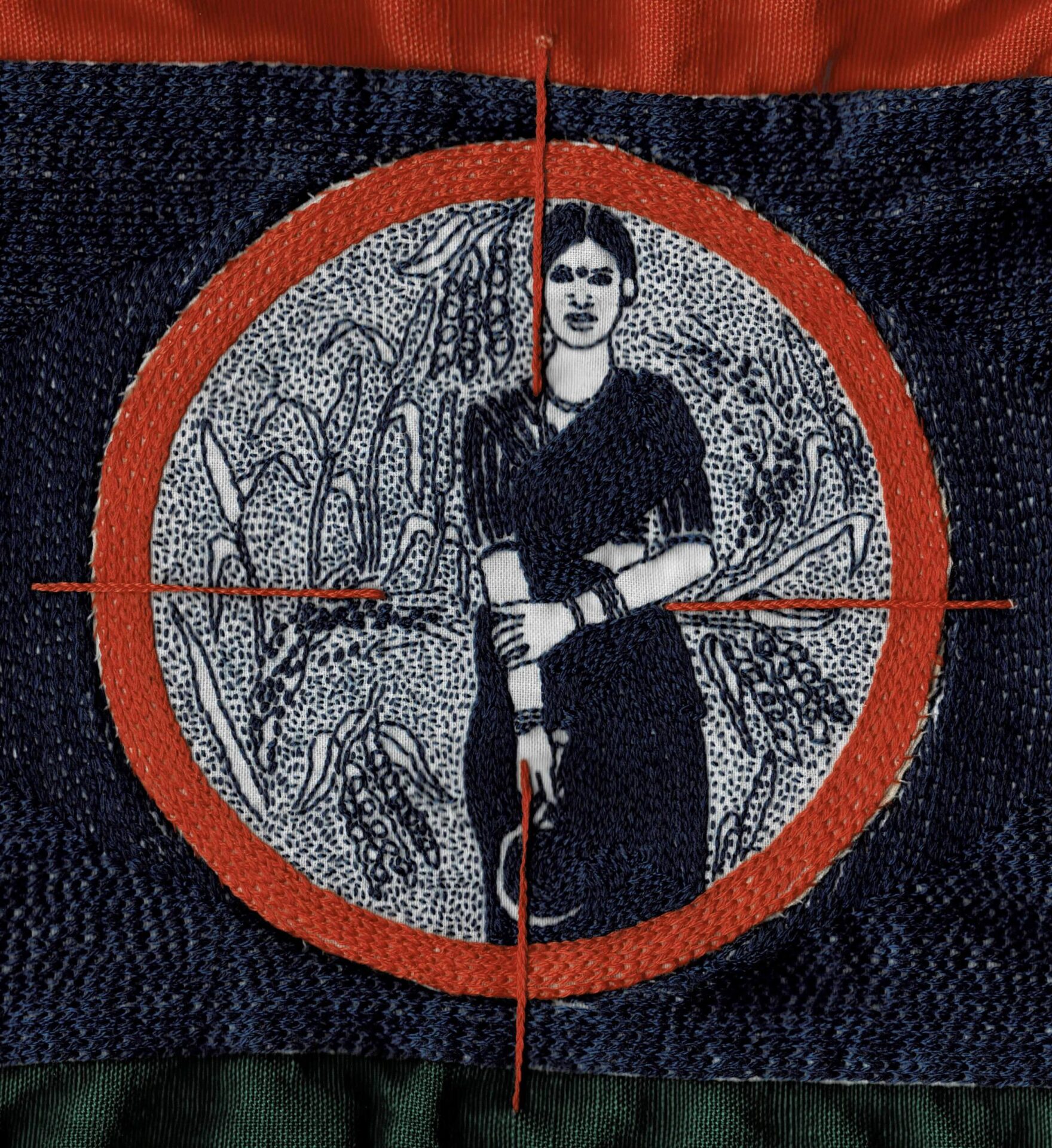

Part of a continuing series, each of these flags of JatiIndia (my name for this country of jatis/castes) features a face of resistance to upper-caste violence and injustice. The color orange symbolizes Hindutva politics; blue—a color historically adopted by the Dalit movement—here represents the country’s Dalits, Kashmiris, Adivasis and other minorities; and the bottom green bar embodies the regions ecological foundations endangered by the ideology of extractive capitalism. The circular image, replacing the Dharma Chakra (Wheel of Law), signifies the view through the crosshairs of a saffron (Hindu nationalist) gunsight.

The blue strip is done in chain-stitch embroidery, illustrating the long chain of atrocities that have been carried out by JatiIndia over the years on its own people, and the people of occupied Kashmir. Each blue chain-stitch, of which there are more than twenty thousand, represents a face of resistance.

.

.

The JatiIndia flags featured here are portraits of a man farmer and a woman farmer surrounded by their crops and maati (soil) and water. That’s the front of the embroidery, representing a romanticized version of India, easy on the eye, where the ecosystem might seem a little disturbed but not threatened to the point of annihilation. And that’s why I’ve also included the back of the embroidery which I hope might communicate that which we don’t see and that which has been happening for decades in rural India — the systemic and institutional structure of violent government policies that have left us processing statements like that of R.S. Amaresh: “If it continues like this, a day will come when there will be no farmer.”

This matrix stitches together a simultaneous kaleidoscopic pattern — one carefully crafted and intentional and the other its opposite. It’s of course impossible for us to see both, the easy front and the hard back at the same time. And we never will. Not unless we are willing to give up our lifestyles that rest on the backs of farmers like Amaresh and Ojha. They are what we eat.

,

Why did [migrants] leave their villages in the first place to come [to the city]? And that was something called the agrarian crisis, which the media chooses to underplay, ignore, until it cannot…[and] what is rural distress? Rural distress is not just about agriculture… The handlooms plus handicrafts sector is the biggest employer in your country [after agriculture]… You know, if you look at the farm suicides, you’ll find, in many parts of this country, farmer suicides were preceded by weaver suicides… Why? When the farmers went bankrupt, the weavers lost their [first] market… These are allied professions… Your carpenters, weavers, potters, honey-hunters, fisherman – all those people are in your agrarian economy… So, if the economy of agriculture tanks, they are finished… When the lockdown came, people were making their way back to the villages, looking for those livelihoods which India had spent the last 25 years killing… What did COVID-19 do for you? It did a complete and thorough 100% autopsy on the society you are, on neoliberalism, on capitalist development under neoliberal capitalism; every nerve, sinew, bone, artery, vein is on display where it’s very ugly, including the maggots… That’s why I’ve said often, the UPA [past government] was the gang that couldn’t shoot straight. The NDA[current administration] is the gang that can’t stop shooting. Every direction, everywhere, anything it can hit. — P. Sainath, The Wire, September 23, 2020.