IN 1962, AS a young and rather aimless woman, I was hired by the Oakland Tribune to learn typesetting on the TTS — TeleTypeSetting machine — which attached a misbegotten contraption to a keyboard that punched holes into a sturdy ribbon. The ribbon was later fed into a similar misbegotten contraption on a Linotype, where it was set into actual type. That poor baby did not live long.

I thought it would be “exciting” to work in a newspaper. And indeed it was. I don’t recall what I earned in former jobs as a typist, but I can tell you I earned a lot more as a printer!

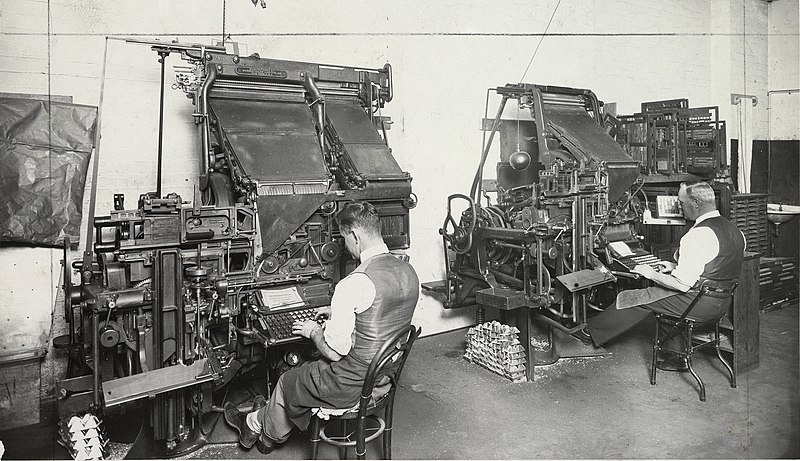

I was totally delighted and attacked the TTS with great enthusiasm. There were a handful of others in the TTS department, maybe six or eight per shift, but there were still far more men on the Linotypes. I was told they did not want to learn the new machine because the Linotype keyboard was so different. But I think that, in addition, Union members were resisting the contract in the only way they could.

In fact, the Tribune was trying to “loosen the cord” that bound the company to the Union. When they brought in the TTS machines and linotypers refused to switch over, the Tribune got the upper hand. They insisted on a provision in the contract that allowed them to hire off the street trainees for the job. And they hired me.

Linotype operators weren’t happy; but they themselves had replaced earlier hand-set typographers; there was little they could say. Over time, the TTS area in the composing room continued to grow, and the linotypes slowly faded away. Those operators moved to other jobs on the floor — as ad or page makeup, into the press room or other departments. Some moved to small commercial shops which still used the outdated letterpress equipment.

During a couple of months’ training I was introduced by members of the International Typographical Union (ITU) to the real role I was playing in a whole new technological revolution as it was transformed from “hot metal” to “cold type.” They also set about “educating” me to the true benefits of Union membership, and once I reached the required level of speed and accuracy, I was eligible to join.

Want to join the union? “Oh, hell, yes!” To earn scale wages? “Yes, Sir!” To get a traveling card? “You bet!”

Tramps

Printers who carried a Union card could pick up work anywhere, filling in for sick or absent workers, or even being given a job simply because there was more work than the current staff could handle. The versatility, portability, and viability of a life on the road for a printer made it an attractive reality to many who possessed a wandering nature. Others were driven by lack of local work.

And so they became known as tramp printers — for “tramping around” the country, following the ancient traditions of itinerant scribes. The term “tramp” didn’t have a disparaging connotation — much — it merely reflected the ancient practice of the itinerant who traveled from town to town carrying ink and vellum to write letters for an illiterate population.

When I got my official ITU card, I promptly quit the Tribune and went to the San Francisco Chronicle, slipping up on the board there as a “journeyman” typographer. I still had learned only a little of what the printing craft was really about, but over the years, I learned many different printing operations. I also heard many tales about tramp printers and learned about the Union’s history. Above all, I learned about the personal benefits of being an ITU member.

In San Francisco, I found out how very easy it was to travel the Yellow Brick Road. The notion of craftsmen being footloose and fancy free is not a common one in the history of labor. Most workers desire stability, placing high value on steady employment, especially in this age of precarity. The peripatetic nature of printers was encouraged by ancient traditions, but also by early American tradesmen. It was through travel and work as a “journeyman” printer in different shops that added to my knowledge. I became a tramp printer myself for about three years — once I discovered the magic of THE CARD.

The Union Card

From very early beginnings, U.S. typographers promoted an equality of membership in their union. This tradition was sealed in the 1852 Constitution of the National Typographical Union. But the tradition began in the early colonies, as early as 1620, when the nation’s first strike was called. This tradition, too, carried over from a long history dating from ancient Greek and Roman times, when craft guilds called collegia formed to guarantee equal wages, rights of workers, and the common good.

By 1869, when the International union was formed, members debated most the important issues — qualifications for membership, wage scales, and rule by member-approved laws. But they had also absorbed a lesson from many earlier strikes — that if they didn’t allow women and Blacks into the trade, owners would use them as strikebreakers. These issues were turned over to the locals, but by 1879, it was written into the Bylaws that a duly-attested ITU Card was to be honored — regardless of race, national origin, culture, gender, or age — with full wages and privileges. Violations of the bylaws received two instances of warnings with hefty fines; a third violation resulted in expulsion from the union.

A new journeyman got a Union Card, proof of status as a qualified union member. A printer could travel anywhere in the world, provided one had that card, the shop was organized, and the member could speak the language.

If you didn’t like the shop, or the boss, you could quit on the spot and immediately “slip up” in another newspaper or shop in another part of town, or another city, or another state — sometimes before the sun set. That card was proof that we were genuine, dues-paying ITU members.

That card was more important to me than a driver’s license or my passport. It gave me a vocation. It gave me a profession that I could feel proud of. It gave me free choice, in most instances, of how often I worked and where I worked. After about a year, I got my Traveling Card from the Union Secretary, left The San Francisco Chronicle and slipped up at the Chicago Sun Times as soon as I arrived. Work then was always available at newspapers.

There were no phone calls inquiring about work availability. There were no interviews required, no irrational questions: “Are you married? Have children?” (No one asked MEN about those issues!) There were no applications to fill out, or long lists of previous employers and job descriptions to submit, no having to account for every day of your working life. You simply showed up and slipped up. Handed your card to the Union Chairman of the chapel and went to work that very day if work was available. How sweet can it get?

Working on the Floor

The Chapel Chairman ran the Composing Room. I mean he — or she — ran the thing. The term

“chapel” just means “shop,” and the “chairman” is the same as shop steward. The ITU is known for its peculiar jargon. In the 1600s, when men worked seven days a week, 12 or 14 hours a day, the only time they were given off was Sunday mornings for church. Naturally they held their secret organizing affairs during those precious two or three hours! “Hey, boss, I’m headed off for Chapel!”)

Chairmen were workers voted for the position from the floor. They knew the issues. They took control of the chapel, hired additional workers from the slip-board. If the worker was in some way impaired, the Chair would not allow that person to work. He/she controlled the hiring of the staff. Not the boss! There was usually a foreman on the floor, who was hired by the “boss” (usually the owner) but he did not order you about. Under the contract he could not! He had to talk directly to the Chairman, and if the chair thought it necessary to correct your attitude or your work, only the Chair could do it.

If the foreman doubted a new sub’s competency (or sobriety), he could order that the sub be “duped” — meaning a letterpress print of everything completed during one shift was copied and given to management. But you were slipped up from the slip board by the Chairman, no questions asked (except maybe, “Do you want to right start now?”).

This did not mean a free pass to laze around, however — you had to do your “fair day’s work” — you could be hired on the spot, but you could be let go just as quickly! The foreman could fire a worker, but such cases were almost always challenged by the Chair.

Substitutes would come any day of the week, or any time of the day or night, and “slip up” — put their names on the chapel slip board — as being available for work. If you were on top of the board, and your slip was “open” — you were available for hire.

If you didn’t want to be available that day, or for several days, you “turned” your slip (or more likely, phoned the Chairman to turn it for you), until you felt like working again. The next member down the slip-board would then be available, and so on. Everything was on a priority basis. If a regular full-time employee quit and management wanted to replace him/her, they had to hire the top sub on the board. If that sub did not want a full-time position, the member could refuse, but then had to move to the bottom of the board. In other words, he/she lost seniority.

On the other hand, as a full-time worker, you soon discovered how nice it was to call in sick. You could hire a sub yourself if you or your kid was sick, or something else was going on. EVERYONE was happy! You had your guilt-free day off (minus a day’s pay, if you were out of sick-leave), the sub got a days’ work, and the boss didn’t suffer a short staff.

In a large chapel, like a daily newspaper with 300 or 400 workers on the floor, there was almost always at least a half-dozen people at the board waiting for hire, sometimes a lot more. And there was ALWAYS that time limit — when the presses started to roll. The paper HAD to come out on time — trains and trucks were waiting for the editions to hit the streets. If you timed it just right, you could usually get a hire.

Equality

From the moment I joined the ITU, I had equal pay, equal working conditions, and treatment as equal as any man on the floor. What a sense of freedom that gave!

I had only two jobs before joining the union, but they were enough to prove to me that the position of women in the workplace in the ‘50s and ‘60s meant lower pay than men, being ordered about and assaulted by male bosses — by language and touch — as well as being taught by society in general that being a wife, a mother, and housework were the only important jobs a woman could have. Of course the exceptions were in typically feminine jobs like teaching and nursing. It was humiliating, demeaning, and abusive.

In the composing room, I could breathe! I could stand up and place a handful of slugs into a case just like the man standing beside me, earn the same, and be treated the same. Words simply cannot convey how liberating this was.

Working at the NY Times

Leaving San Francisco with my prized Traveling Card, I partnered with an old-timer, who knew all the ropes and we headed for the Chicago Sun Times by way of the railroad — the famous California Zephyr. After a month, we moved on to Cleveland, and worked the upstate New York route through Buffalo, Rochester, over to Concord, up to Portland, then down to Albany, Providence, Boston, Hartford, and the Big Apple—to the New York Times!

Oh, I loved NYC! I was there in November, 1965, when the lights went out! What a night to remember!

The New York Local was the best! I worked a short six-hour lobster shift at the Times, which included an over-scale wage (due to the wee night hours), and a full hour for “lunch” (instead of a half-hour). That hour was either at the local bar or sound asleep on a “stone” (steel tables for page makeup). I’m not kidding — the lights were turned off, machines went idle, and for an hour, rows of people, mostly men, in printers’ aprons and newspaper hats would just slide cases of type aside and hop up on a stone for a nap. (The term “lobster” originated because of the coincidental timing of seamen setting out in the middle of the night to set their lobster traps.)

When I left New York, I went to D.C. and worked there about 30 days, which was 29 days too many. Never once saw the sun. Should have named it Cloudy City (since Chicago was “Windy.”)

I wanted to work at the Washington Post. What printer doesn’t want to work — at least for a short time — at the NYT and WAPO? I also worked at a “job shop” — if one can so call the Scientific American — for a brief period of time. I loved both D.C. jobs, but the weather got to me and so did other circumstances, so I moved on by myself to Philadelphia, and eventually to Georgia, the Atlanta Journal (one of the very few Union newspapers in the entire South) and spent a month or so, but couldn’t take the climate or the racism rampant there either, and so finally returned to the Bay Area.

“Home Guard”

I’d had enough of the glamour of the road, because I settled down for a while, back at the Chronicle. As soon as a full-time job came along, I took it and became a “Home Guard,” Although I did want to go to sea someday.

As a woman in the ITU, I was never limited to what I wanted to do. I worked when I wanted to, or when, more than likely, I needed income. I mostly worked a four-day week, because I earned enough to live on, and fulfilled my obligation to hire a sub when I saw they needed work. For the first — and only time — in my life, I felt like I actually earned honest pay for the work I did — pay equal to my worth.

Old-timers made younger typographers aware of the costs of aging and the principles of sharing the work. You worked at a steady but even pace — not an exhausting one — so as not to set a standard so high that older people could not match it. Be cooperative, help others. It is not a competition! More apropos, no one should have to work to the point of exhaustion! You might be young and single, but an older or disabled printer might have several kids to feed, and you had no right to jeopardize his job because you were faster. And the old-timer would wink and say, “We are all in this together.”

The rule was “a fair day’s work for a fair day’s wages.” When a full shift of overtime was “hanging on the hook,” and a new sub came in, the sub had the right to claim those overtime hours. The home guard who earned the overtime was “bumped off” for the day so that the sub could claim a day of work. This was to prevent full-time workers from gaining hours and hours of extra pay, while others had no work at all. You shared the work.

There were still plenty of old-timers around and they had my ear! I had many mentors — and some had been socialists for a long time. I began reading political literature, and gradually felt like I was becoming a sophisticated and informed individual. I realized how beneficial unions were to society!

Political Growth in the Union

I became active in union politics and eventually ran for chapel chairman on the night shift (usually around 6 to 12 midnight), and I won. I represented a working staff of about 300 on the floor at the Chronicle for a year. Then I ran for city-wide ITU delegate to the San Francisco Labor Council and won.

In those early days, Viet Nam “advisement” was ramping up to a full-blown war, with increasing numbers of troops being sent overseas. I became active in the peace movement. As delegates to the Labor Council, Anne Draper* and I were booed out of the Hall for co-presenting what I believe was the Council’s first anti-war resolution.

Like many women of that era, I also became active in the woman’s movement, met quite a few feminists, met, with some trepidation, a few Black and Brown Berets (they bore rifles!), and listened to a lot of Free Speech Movement orators on the Sproul Hall steps at the University of California, Berkeley.

Over the following years many printers became active in the Farm Workers struggle to organize the United Farm Workers Union. I collected money from my chapel to provide fresh milk for the infants in Delano, who could not digest powdered milk. Activists from several San Francisco unions traveled by caravan once a month to Delano to deliver food and supplies to UFW strikers. This gave us many opportunities to hear the leaders and organizers of that strike, and leaders from supporting unions, and to join in the fields with striking workers.

Both union and civil rights activists understood that labor rights are human rights, and that to constrain a person’s liberty — to willfully prevent any individual from choosing his/her work, from supporting a family, from living where and how he/she pleased, from traveling freely without restraint — is a deliberate act of coercion — illegal, immoral, and unjust.

Only once was I disappointed by my Union — I found out I could not go to sea on transatlantic or transpacific ships because they only had a single berth and bath — for men. I wanted so badly to go to sea, as a ship’s printer — printing daily news, entertainment available, dining menus and price lists.

Guess I still had a streak of the tramp in me after all. I was so disappointed.

Eulogy

A truly fair and democratic union gives you the opportunity to really experience the power any working human being has — working along with his or her brothers and sisters — for better working conditions and for the very lives and health of all — THAT is the true power of the people.

All the benefits we had, we WON during the bargaining process. We earned what we gained. By standing together and holding out, and striking if necessary, we won the benefits we earned. We had to struggle for those benefits. But together we got them. This is the strongest argument there is for Unionism!

The ITU was a good solid union. It was fair. It was honest. It was democratic. And it had a heart. It was very painful to see it die before my eyes. I do not fault ITU leadership for the loss of the printing industry. It did not fail. Rather, it showed us the way. But the world moves on and the shift to cold type was the beginning of the end of the industry.

There were two factors in the demise of the trade: First was the incredible pace of developing technology, which — not hyperbole — is exponential. The ITU did all the restructuring possible while it could. It was an easy switch for TTS operators to move to IBM typewriters and then to desk computers. But after the onset of home computers, the internet, and desktop publishing, there was no further place to go — there was simply no work left for composing rooms. Eventually even job shops had to face the digital music.

Second, equally devastating, was the deep division that has always stood between free working people who choose to organize and wealthy owners who are willing to sacrifice the health and welfare of common people for personal gain. This animus — an implacable rage against unions by news media in particular — helped in giving birth to mergers that saved the owners, but that decimated the number of newspapers and job shops. San Francisco had a dozen or more newspapers operating in the city during the early 1900s. Now there is one, the “ChronExam,” with essentially one editorial voice, two editions, sans composing room.

The end of this great trade reverberates with the action of the Government Printing Office in 2018: The GPO shipped off the last remnants of its letterpress operation, marked as “hazardous waste” — all its remaining galley proof presses, linotypes, Ludlows, and 300 cases of foundry type, the last physical artifacts of the largest hot-metal operation on earth — for scrap.

*Anne Draper was the West Coast Union Labor Director for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America and before their merger, a member of the ILGWU. She was an active supporter of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers as well as a founder of the Labor Assembly for Peace and Union W.A.G.E. (Women’s Alliance to Gain Equity). The wife of the better-known writer Hal Draper, Anne was my mentor and my friend. She introduced me to the International Socialists (precursor to Solidarity).