What is enough? Put that question to any economist or politician, and you are likely to get a blank stare in return. In a society devoted to continuous economic growth, there is no way to answer the question “How much is enough?” because continuous growth implies there is never enough.

However, given the current climate emergency and the broader ecological breakdown that looms in the near future, there are few issues more pressing than that expressed by the single word enough, whether it’s used with a period (“I think there’s enough to go around.”), a question mark (“How much is enough for a good life?”) or an exclamation point (“Cut it out!” “Enough!” “Basta!”)

The Earth has been telling, asking, and shouting, “Enough?!” at humanity more loudly every year for the past three decades, but the nations of the world have not been listening. The most recent edition of the authoritative United Nations Emissions Gap Report reveals the price we must now pay for our procrastination, or even more, our full-on neglect. It concludes that humanity must reduce the release of greenhouse gases by a whopping 56% between now and 2030. According to the report, the breakneck rate of emissions reduction now necessary is four times as fast as would have been required had the world started reducing emissions as recently as 2010.

The bulk of carbon dioxide overload now in the atmosphere was generated by the long-industrialized nations of the global North, yet the impacts are being suffered disproportionately in the South. Therefore, the United States has a moral obligation to reduce emissions even faster than the global reduction rate that the UN is prescribing. And this partial payment-in-kind on our carbon debt should come in addition to reparations the North already owes for not only climate loss and damage, but also for colonialism, slavery, imperialism, and their associated evils.

To eliminate 56% of annual greenhouse emissions in just the next nine years, as urged by the Emissions Gap Report, it will be necessary to clamp a ceiling on the resource consumption of the world’s affluent while establishing a floor under resource access for those across the Earth who now lack the essentials of a good life. This is at the core of concepts such as “contraction and convergence” (under which the world’s affluent countries would deeply reduce their ecological impact, converging with low-income nations who will be gaining greater access to resources) and Kate Raworth’s “doughnut economics” (in which the world economy must stay in the “dough” between the outer edge of the doughnut, representing critical ecological boundaries, and the hole, which represents deprivation, the lack of basic requirements for a good life).

The emerging emphasis on both lower and upper limits challenges the venerable assumption, dominant in affluent economies, that unrestrained wealth accumulation is the key to providing everyone sufficient access to basic human needs. That assumption fails perhaps most spectacularly in the U.S., where the Gross Domestic Product, adjusted for inflation, has chalked up increases in 67 of the past 70 years as it climbed a colossal 800%, while 14% still live below or near the poverty line— only slightly below the lows reached in the 1970s. An estimated 35 million were enduring food insecurity before the Covid-19 pandemic, and the number has increased since. An upending of the inequitable growth economy is clearly overdue.

Given the alarms being raised by climate science, high-consumption societies cannot achieve ecological healing unless we practice an unprecedented degree of collective restraint in resource use. Adapting to that new reality will require that we set aside the pursuit of growth in order to end ecological destruction while still ensuring sufficiency for everyone. That can be done—but only if material resources and products are valued not as ends in themselves but for their essential role in securing fulfillment and well-being.

The Elements of a Decent Life

Three decades ago, the late Chilean economist and Right Livelihood Award winner Manfred Max-Neef argued that the basic needs of human beings go deeper than the list of goods and services that usually comes to mind. He identified nine underlying universal needs, among them subsistence, protection, participation, creation, and freedom. Our need for subsistence, the means of sustaining life, must of course be satisfied before the other needs can be met. That’s why lists of basic requirements always include food, shelter, health care, etc.—what Max-Neef termed “satisfiers” of needs. The needs are the same among humans everywhere. The satisfiers vary and shift over time and from place to place, but each society’s goal, he wrote, must be universal satisfaction of our fundamental needs. Based on what we now know in 2021, we should add that those needs must be satisfied without violating the Earth’s ecological limits.

Is it possible to draw up a list of goods and services that would satisfy humanity’s universal needs? Given Max-Neef’s observation that satisfiers change over space and time, we should maybe narrow the question and ask, “What would be minimum satisfiers, worldwide, in the 2020s?” Narasimha Rao and Jihoon Min of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis have attempted to answer the question by proposing global “decent living standards” required for human well-being.

In the standards, Rao and Min included adequate daily consumption of calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals; adequate means of food preservation, including a “modest sized” refrigerator; cooking equipment that does not pollute the indoors; an adequate, safe, reliable water supply; a solidly built home with adequate floorspace; electric lighting; thermal comfort; good indoor toilets; electricity, water, and sewer services; sufficient clothing and access to laundry facilities; and freedom to peaceably assemble in spacious, well-lit public spaces.

“Enough” in terms of these minimum requirements is far from being fully realized in the world of 2021, even in affluent nations. Therefore, in addition to proposals for “universal basic income”—a monthly, unconditional stipend paid to every household—progressive movements in the U.S., United Kingdom, and elsewhere are advocating for “universal basic services.” The principle is to guarantee every individual and household sufficient and continuous access to goods and services that are essential, not only to individual well-being but also to the collective good.

Universal basic services may include, for instance, public water and energy utilities; health services; public education and transportation; affordable, culturally relevant, healthy food; high-quality housing; green space, clean air, and public safety without repression. Securing access to all of that for all households, regardless of their ability to pay, is well within the ability of governments in high-income nations, if the political will can be mustered. But universal basic services are out of reach in countries where, after centuries of colonization, imperialism, and exploitation, most people lack sufficient access to resources, especially energy. That must change.

Global Energy Justice

In our greenhouse future, the questions “What is enough?” and “What is too much?” are becoming increasingly urgent when it comes to energy. In stressing that the world must immediately begin decreasing emissions by 8% annually over the previous year’s emissions the Emissions Gap Report points out that more than three-quarters of global greenhouse emissions come from fossil fuels. It’s clear that the climate emergency will continue to escalate until we choke off all oil, gas, and coal use—a daunting prospect, but one that’s possible, given how much progress organizations, movements, cities and even states are making. The success of First Nations-led struggles against oil pipelines and other fossil-fuel infrastructure is one of many examples.

The phase-out of fossil fuels must be managed in a way that sustains lives and livelihoods worldwide, including in regions that already lack sufficient supplies of energy. That will be possible only if economically stressed communities around the world can acquire resources for building renewable energy capacity sufficient to meet every household’s needs.

Narasimha Rao and his colleagues have shown that given dramatic technological progress—especially in renewable energy—and full equality of access to resources, the bare minimum global energy flow required to achieve universal decent living standards could be as low as 15 gigajoules per capita per year (or in more familiar terms, 500 watts per capita). Aiming for much less ambitious reductions in energy demand, the International Energy Agency projects that the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals can be achieved worldwide with an energy flow of about 1,300 watts per capita. That’s comparable, for example, to the supply of energy in Cuba today.

According to World Bank data, dozens of nations fall far short of IEA’s 1,300-watt minimum. Among Cuba’s neighbors, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Honduras average less than 800 watts per capita. Philippines, Vietnam, and Cambodia average less than 700 watts. On average, the Sub-Sahara African nations of Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Ghana, and Democratic Republic of the Congo live on less than 600 watts per person. Likewise in South Asia for Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Pakistan. Those are national averages; thanks to highly unequal energy access within nations, countless communities live on less than the bare minimum of 500 watts, getting nowhere near 1,300 watts.

At the other end of the energy scale, the United States and Canada consume more than 9,000 watts per capita, seven times the IEA’s sustainable-development standard and 30 times the per capita energy use of Bangladesh. Such extreme disparities cannot be corrected by raising global energy consumption to the profligate U.S. rate; that would be physically impossible. Instead, availability of energy from renewable sources must be expanded dramatically in nations that today fall short of what is necessary, while at the same time, energy from non-renewable sources must be rapidly phased out in high-consuming nations—a classic case of contraction and convergence.

Coming together

To achieve sufficiency and fairness, all regions and nations could aim initially for a modest target, for example, total energy flows of 2,000 watts per capita, fossil free. That vision has long been proposed by the 2,000-Watt Society movement for reducing the global North’s ecological impact. Then, as decades pass, improvements in energy efficiency and conservation could help further reduce energy demand.

Here in the U.S., transformation of such scale will require immediate, direct, dramatic federal action. The headline goal of suppressing greenhouse emissions by at least 8% per year will require a statutory cap on the number of barrels of oil, cubic feet of gas, and tons of coal allowed out of the ground and into the economy, with the cap ratcheted down dramatically year by year. A parallel buildup of renewable electric capacity, while urgently needed, will almost certainly not be able to keep pace with the decommissioning of coal- and gas-fired electric power stations, let alone the phase-out of fossil fuels in manufacturing, transportation, and agriculture. A U.S. economy striving to bring carbon emissions down to zero will have less energy to work with; consequently, it will not be a growth economy.

In May, the IEA concluded that restricting greenhouse warming to the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5 degrees Celsius while sustaining steady growth of the world economy would require energy efficiency to increase at three times its current rate of improvement, a historically unprecedented rate that, even if achieved, is highly unlikely to reduce energy use and emissions as much as is needed. Furthermore, almost half of the emissions reduction envisioned in the IEA’s low-emissions growth model over the next three decades would have to come from technologies that are not only unproven on a global scale—they have not even been developed yet.

IEA’s model falters because it aims to sustain worldwide economic growth and, by implication, excessive energy demand. In a recent published modeling paper, Lorenz Keyßer of the University of Sydney and Manfred Lenzen of ETH Zürich found that only a scenario in which the economies of the world’s rich nations stop growing and contract can greenhouse warming theoretically be limited to 1.5 degrees without assuming unrealistically rapid, technologically tricky, and ecologically risky rates of renewable energy development, efficiency increases, and carbon capture.

If we, in the U.S., undertake a sufficiently rapid phase-out of fossil fuels, we must be prepared to live with a diminished energy supply. Consequently, the federal government would need to make sure the economy continues to satisfy basic needs. The most direct and effective means of doing that would be a comprehensive industrial policy that directs energy and other resources toward the production of essential goods and services and away from wasteful and superfluous production.

Such policies could include less military production and more restoration of ecosystems; fewer planes or private vehicles and more public transportation; fewer McMansions and more affordable, durable housing; less feed grain for cattle and more production of grains and legumes that people can eat; and an end to production of luxury goods, in favor of basic necessities.

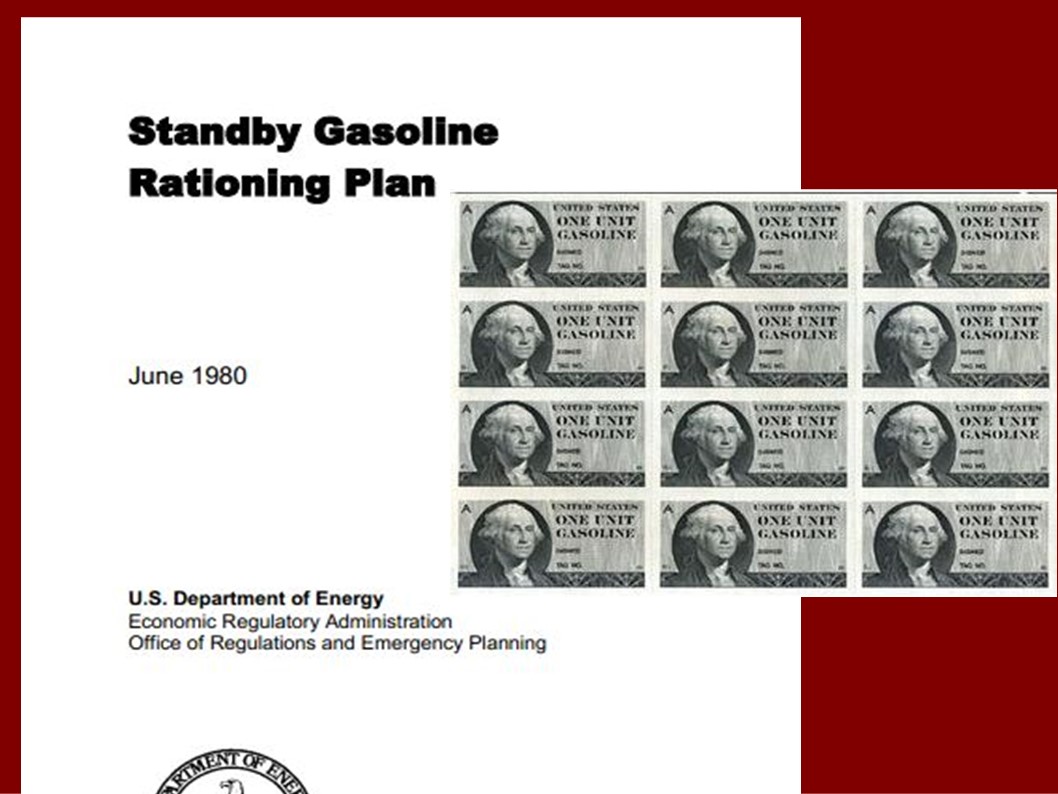

Meanwhile, a guarantee of sufficient, fair access to electricity and fuels for every household would be required. With a constrained energy supply, the fairest route to ensuring that all households have enough electricity and fuels would be through price controls (to keep energy affordable) and fair-shares rationing (which would be based on our requirements for a good life and not our ability to pay, which is the customary rationing criterion).

Adapting to a shrinking energy supply while we wean ourselves from oil, gas, and coal is within our capacity, but it won’t be easy or straightforward. For decades, our entire society has been arranged around an assumption that the fossil-fuel bonanza of the 20th century would roll on through the 21st. Now we know that can’t happen. Running society on less energy will mean grappling with the legacies of suburban sprawl and commuting culture; homes, offices, and commercial spaces that were built for a world of unlimited access to energy; and an economic system that depends utterly on ever-increasing production and consumption.

In an energy-limited society, the question of how much is enough will be complicated, to say the least. Given the gross inequality of life circumstances in U.S. society, equal energy access doesn’t translate into fair access. For example, residents of rural areas, as well as those in and around cities who cannot afford to live close to their workplaces (and don’t have access to good public transportation), will require more motor fuel than people who don’t have to drive as much.

Millions of renters and low-income homeowners who are stuck in poorly insulated, drafty houses and apartments will need more electricity or natural gas than others. Likewise, many households cannot afford energy-efficient vehicles or appliances, let alone rooftop photovoltaic panels. Until our society resolves these and other structural problems, “enough” for some will be insufficient for others.

Clearly, adapting our economy and culture to a smaller energy supply while maintaining an adequate, universally equitable flow of essential goods and services will be a challenge. But we should look at it this way: If we manage to start the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels, the most formidable hurdle will have been cleared. That successful first step will create a wholly new reality, motivating us to abandon the lazy complacency of the fossil-fuel era and find new ways to satisfy human needs, with no one left out.

Fair shares for all

Rationing is too often caricatured by climate deniers and fuel-industry flacks as something the government will impose in order to restrict our personal consumption, with the goal of reducing society’s total demand. That’s an upside-down view. Rationing is not a means of reducing consumption but rather a response to an existing shortfall. It’s an adaptation aimed at securing both sufficiency and justice, guaranteeing everyone a fair share.

Planned resource use, price controls, and rationing all may seem alien to the current U.S. economy, but they are in fact important pieces of mid-20th-century American history. During World War II, with the increasing restriction of energy flow and other critical resources into the U.S. civilian economy, the government adopted sweeping measures to allocate resources toward essential goods and services, ban unnecessary production, and guarantee universal, fair, equitable access to food, energy, and other essential needs through price controls and rationing. These production, price, and rationing regulations were announced to the public through a weekly Victory Bulletin published by the federal Office for Emergency Management.

Achieving those goals required that an umbrella of federal policies for resource allocation and fair-shares rationing be consistent nationwide. In addition, for the umbrella to be broadly accepted, the citizens who would be living under it also needed to have some degree of community control and flexibility. To satisfy that need in the 1940s, the Roosevelt administration created a nationwide network of more than 5,600 local rationing boards.

The local boards distributed coupons for food products, shoes, tires, fuels, and other rationed goods to each household in their county or other area, in federally prescribed quantities. The Office of Price Administration, which oversaw price controls and rationing, also provided each board a supplemental quota of coupons, primarily for motor fuels and heating oil, to be distributed in fair proportions to families who demonstrated the greatest need for extra rations.

In a history of wartime rationing written for the Roosevelt administration, Emmette Redford noted that having local citizens as the face of the rationing system “was the most effective means of obtaining favorable community sentiment” regarding the need for collective restraint.Sadly, however, giving rationing a local face was not enough to guarantee a just, democratic process.

Members of rationing boards were appointed by federal officials, not elected. Each board was supposed to be representative of the community, and with respect to gender and occupation, they mostly were farmers, merchants, and, in the gender-hindered terminology of the day “housewives,” making up the largest shares of board membership nationwide. But with the culture still rooted firmly in the Jim Crow era, fewer than 1% of board members were Black.

If the U.S. were to quickly begin phasing out fossil fuels, fair-shares energy rationing under local governance would be just as crucial as it was 80 years ago; clearly, however, any such system would have to be much more equitable, inclusive, and small-d democratic than in the 1940s. Energy rationing could be accomplished electronically, which would make it much less cumbersome than it was 80 years ago, when boards had to distribute countless coupons to their local residents, who handed them over to merchants when buying rationed goods. The merchants then returned the coupons to the rationing board.

In proposals for future energy rationing, it is envisioned that households would instead have energy accounts, analogous to bank accounts, into which the government each week would deposit ration credits denominated in quantities of fuel or electricity, not dollars. Credits would then be deducted from a customer’s ration account via smart-cards at the gas pump or at the time of paying utility bills. Energy-frugal households could either save their unused credits for future use or sell them into a ration pool from which they could be equitably distributed to households that require additional credits.

The redistribution of credits from the unused pool could be carried out, for example, by locally organized cooperatives that reflect their community’s diversity in all its dimensions and operate under principles of equity and deliberative democracy. To help stretch ration allowances further, the cooperatives should also receive ample state and federal funding to improve home insulation and energy efficiency for low-income households, and for the community to expand free public transportation.

Although every community across the nation would be playing by the same overall rules, greater local autonomy could be achieved by designating a pool of collective fuel and electricity rations to be allocated by the community as a whole for the common good. Deliberations over energy resources should include voices from all sectors and have as a top goal to make reparations for past inequities in access to resources.

Other models of local resource stewardship could be useful guides. For example, “participatory budgeting” has been practiced at times in progressive cities around the world. The process unfolds through successive rounds of democratic deliberations in which residents develop budgets for using public funds in their own neighborhoods and communities. Emphasis is generally placed on improving resources and services in previously marginalized neighborhoods. It would seem that if money can be prudently and democratically stewarded by the people and for the people in such a way, then so could energy and other essential material resources.

We can also look to local efforts that aim for a broader transformation. For decades, the U.S. environmental justice movement, led by Black, Latino, and Indigenous communities, has won improvements in health and quality of life by fighting the electric utilities, fuel refiners, cargo transporters, and other dirty industries that ruin their neighborhoods’ air and water. Indigenous struggles of the past few years have been a bulwark against the degradation of tribal lands by fossil-fuel extraction and oil and gas pipelines, boosting and energizing the entire climate movement.

There are many other examples of how to achieve systemic change with equitable sharing. None of them is a panacea; for such complex issues, there’s never a universal solution. Instead, a proliferation of local and national efforts is required—and fortunately, a thousand flowers are already blooming. We have available a wide variety of strategies that can help societies ask, answer, and act on the questions, “What is enough?” “What is too much?” and “How can we keep the Earth livable and achieve sufficiency for all?”

Stan Cox is a research Scholar in Ecosphere Studies at The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas. He is on the editorial board of Green Social Thought and author of The Green New Deal and Beyond and The Path to a Livable Future (November 2021).