Neo-colonialism and increasing Inequality in the Global South- Focus on India

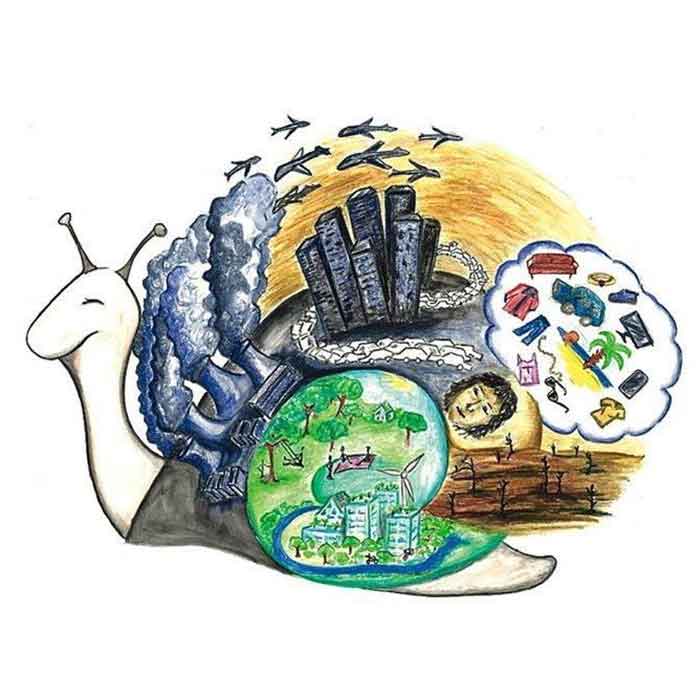

“The Billionaire Raj is now more unequal than the British colonial Raj,” read a tweet by the World Inequality Lab quoting the findings of their new paper on income and wealth inequality in India from 1922-2023. The findings of the report reveal colossal gaps between the people who hold top 1% of income and wealth in comparison to the middle 40% and the bottom 50%. The top 1% in India as of 2022-23 hold 39.5% of the wealth share and this is five times the share of the bottom 50%. What is most intriguing is the wealth shares of both these groups (the top 1% and bottom 50%) was identical in 1961 and most of the gains to the top 1% came post 1991. Today income and wealth shares of the top 1% are at a highest historical levels and India’s top 1% income share is higher than South Africa and Brazil. And according to the same report we observe a reverse trend for the bottom 50%, where their wealth and income share has reduced in 1991 and stayed stagnant with no signs of an increase.

The year 1991 was significant as the new Government in India brought a series of policy reforms that liberalized the economy and opened it up to the world, moving away from an approach of self-reliance to market and consumption oriented. This was prompted by the balance of payment crisis since the mid-1990s and according to the World Bank was due to the poor performance of the public sector and over-regulation. In order to support India’s path to this sustained economic growth, the World Bank provided India with its first Structural Adjustment Loan/ Credit, with a caveat that India will be committed to an economic reform that liberalizes the trade regime, promotes foreign direct investment and strengthens institutions of capital markets. While to some this may seem like a generous offer from the international community to support India in its economic transition, I would like to refer to a term coined by Kwame Mkrumah in 1965, “neo-colonialism”, to describe this relationship. Neo colonialism is one of the basic causes of this grotesque inequality in India that is reflected in the report of the World Inequality Lab. Neo-colonialism is rooted in colonialism, that creates structure of dependency critical for domination and economic structures are a central part of this dependency.

Decolonisation of the economic imaginations of the Global South

India’s economic imaginations and theories are captured by colonial epistemologies and imperial science that reduce the world as an object of extraction and exploitation controlled by white male bourgeois and their accomplices (Lang, M, 2017). Ngugi wa Thiong’used a concept called the “cultural bomb”, which is described as an annihilation of people’s belief in their names, language, environment, heritage, struggle, unity, capacities and ultimately in themselves. The cultural bomb is an apt phenomenon to describe India’s embracing of neo-colonialism policies to solve for the economic crisis of the late 1980s-90s.

In order to see beyond this economic imagination limited by Eurocentrism[1], we need a radical decolonisation agenda in India that questions the very building blocks of economic theory that subordinates societies that were former colonies and facilitates new forms of colonisation. Decolonisation is an important mental and thought process that rejects dominant world beliefs of how the world functions and replaces it with alternatives.

But decolonisation of economic thought is not just the need of the hour in India, but across countries of the Global South that are encouraged to imitate the development of the Global North.

Degrowth & Decolonisation

Degrowth as a concept plays a critical role, as it provides the space for plurality of worldviews to thrive and Decolonisation is one the clearest ways to build this plural world. Despite degrowth being a powerful concept to transform the imagination and infrastructure that is oriented towards linear growth produced by capitalism (Barbara Muraca 2014). It has failed to address economic growth as a global phenomenon thereby failing to challenge colonialism and it is limited to a proposal for the Global North, by the Global North. This is a rather large lacunae in the thinking of the global degrowth community, as ecological economist Clive Spash points out at the fifth international conference of degrowth in Budapest that economic growth is not a solution for the Global South and this model produces inequality, pollutes cities and makes self-sufficient rural communities dependant.

Spash goes on to further state that “ the material wellbeing of a minority that has managed to climb up the social ladder to the middle class is only possible at the expense of a majority of the population that remains in poverty” (Spash 2017). I am sure Spash’s words emotionally connect with many of us living in the Global South and are also reflected in the recent report on India’s inequality by the World Inequality Lab. While I appreciate what is written by Giorgios Kallis, Federico Demaria, and Giacomo D’Alisa in their book Degrowth — a vocabulary for a new era (2015), that degrowth is a conceptual space for communities and cultures in the Global South to explore what is considered a good life. I believe the degrowth community can do better by exploring the intersections between degrowth and decolonisation more thoughtfully.

Decolonising Degrowth

Taking inspiration from Samir Amin’s explanation of what is meant to be a Marxist (1990), “it is not to stop at Marx, but to start from him.” I would like to propose a decolonising degrowth agenda which is not to stop at degrowth but to start from there. Furthering this thought and borrowing from the idea that is expressed in Amin’s book, Global history: a view from the South, there is a reference of an epistemic intervention of rewriting human history from the perspective of the Global South and a de-Europeanisation of global history. Similarly, in the decolonising degrowth agenda, degrowth will have to be understood from the perspective of the Global South and not reinforce dominant understandings and colonial epistemologies limiting Global South to a few case studies of good living. This would mean, that degrowth thinking would need to start from the South to the North and strongly correlate linear economic growth with Eurocentrism which is a polarising global project reinforcing imperialism and inequalities and failing to recognise the post-colonial experiences of capitalist development (Amin:1998/2009 & Sanyal 2007). The reason I started this article with the example of India’s economic growth, neo-colonial policies and related inequalities, is to further think through two questions relevant to the decolonising degrowth agenda: 1) What parts of the economy need to degrow in the Global South that are a result of post-colonial experiences resulting in heightened inequality, 2) Understanding re-westernisation in the Global South between the bourgeois elites and countries of the Global North and the need to challenge this through decolonisation and regrowth.

[1] According to Amin, Eurocentrism is the world view fabricated by the domination of Western capitalism that claims European culture reflects the unique and most progressive manifestation of the metaphysical order of history.