Capitalist society has a dynamic tendency towards constant technological change — change in products, methods of production, and in the ways workers are managed in the production process. I am going to suggest that capitalism has a very distinctive way of developing technology that is inherently conflicted — it provides human benefits but is also highly destructive in various ways.

Capitalist firms make money by producing commodities they sell to us. Many of these products are things we do want to have produced — drugs that help to lengthen people’s lives, food we consume, clothes we wear, houses we live in.

Since labor is a primary expense for firms, they work to reduce the number of worker hours it takes to produce a unit of output. Over time society’s productivity increases. This does not automatically lead to a higher standard of living for workers because the owning class doesn’t voluntarily share its loot with the working class. But a higher level of labor productivity does make it at least feasible for workers to gain increased compensation for their work if they form unions and engage in strikes and other forms of mass resistance to exploitation.

But capitalist technological development also has its dark side — degradation of work, destructive effects on worker health from workplace injuries, stress and chemical exposures, and an increasingly severe crisis of environmental devastation. The destructive character of capitalist technological development is rooted in autocratic control and exploitation of workers and a constant tendency to externalize costs onto workers, the larger community, and nature.

But what is technology? Technology is not just hardware and software. Rather, technology is systematized practical know-how — based on some body of knowledge such as science or craft knowledge — which enhances the ability of society to produce goods and services people want, and which is embodied in human skills, forms of work organization, and equipment and software.

There are those who look primarily at the positive contribution of capitalist technological development, and see only a drive for “human progress.” Among socialists there are those who think the problem with capitalist technological development is not the technology it does develop, but its failure to develop production of goods and services that are desirable but not profitable. This idea of capitalist technology as “progressive” and “class-neutral” or “socially neutral” is called productivism.

For socialists who hold this view the goal of socialism is to “unleash production” from the “fetters” of the capitalist profit-motive. As Matthew Huber and Leigh Philips — contemporary productivists and growth enthusiasts — put it, socialism “releases production from those constraints….As markets limit production to merely the set of things that are profitable, socialism always promised to be so much more productive than capitalism.” Thus they do not critique the technology that capitalism does actually develop, but it’s failure to develop production of things that would be socially beneficial but not profitable. This implies that the existing capitalist technological development is not inherently antagonistic to working class interests.

Capitalism and Technology

To understand the inherent effects of capitalist technological development on the working class, we need to look at the basic dynamic of technological change under capitalism.

Competition drives firms to constantly seek to minimize their expenses per unit of output. Thus, firms constantly work to reduce the number of worker hours per unit of output because the reduction in labor expenses per unit is a key to making profits. When firms hire workers, they are renting our capacity for work. But there is a basic clash of interests in how these capacities are used. Workers have an interest in higher compensation, an easier pace, a safer work environment, time for social interaction with colleagues, less intense supervision, and more opportunity to learn and apply skills. But this runs up against the interest the firm has in reducing its wage bill, suppressing unionism, and a more intense pace of work to get more production per worker hour.

This conflict of interests is the basis of a fundamental antagonism between labor and capital. Workers resist management decisions in various ways. They work out shortcuts to gain moments to relax or they band together and form unions and engage in disruptive actions such as strikes to resist management power. And thus technological development in the contested terrain of the capitalist workplace also motivates another feature of capitalist technological development — the development of management strategy and tactics for controlling workers. Because control over labor affects output and profits, it’s another feature of capitalist technology.

The factory system was not initially introduced in the 1800s as a basis of change in tools or skills, but as a worker control strategy. The early “putting out” system in the 1700s saw merchants use their funds to contract with artisans to produce goods in their cottages or workshops, using their own skills and knowledge of production. This enabled the artisans to control the pace of work. They also sometimes kept some of the materials to make goods they sold on their own. From the point of view of the capitalists, this method of production was too slow, costly and unreliable. Requiring workers to come to work at a factory meant the owners could set up their own system of supervisors to push the pace of work. They were able to greatly extend the working day, forcing out more production. And they could prevent theft of the materials. Very often these early factories used the same skills and tools as the artisans had been using on their own. The technological advantage for the capitalist was in the method of controlling workers, which did increase productivity — at a cost to workers of a grueling pace of work and sometimes unsafe conditions. The vast extension in the working day then became the target of the working class shorter-hours movement. Since technological development includes methods of work organization that enhances productivity, these capitalist methods for controlling workers were an aspect of capitalist technology.

Over the course of the past century, corporations systematically developed and applied techniques of work organization and job design that enable them to intensify the pace of work, minimize worker hours per unit of output, and require fewer workers with scarce skills. All of these things help to expand productivity and reduce the wage costs per unit of output. Back in the early 1900s a number of “efficiency experts” like Henry Ghent and Frederick Winslow Taylor developed an approach they called “scientific management.” By the 1920s this had become standard practice among American corporations. This became the basis of the occupation called “industrial engineering.”

According to Taylor, the key to economic “efficiency” was “task” analysis — analyzing a worker’s job into discrete steps, carefully examining how long it takes to do each task. Taylor’s ideas are thus associated with the use of a stopwatch to time the work. If a skilled worker is performing a relatively simple task that could be done by a person with less skill, then a separate job might be created, and someone would be hired to do that task without also doing the tasks requiring the more extensive expertise of the skilled technician. Because a less skilled person could be hired at a lower wage, it would reduce the company’s expenses. An essential feature of “scientific management” is taking away from workers as much as possible the conceptual, planning and decision-making tasks. “All possible brain work,” Taylor wrote, “should be removed from the shop and centered in the planning or lay-out department.” “The work of every workman,” wrote Taylor, should be “fully planned out by management…not only what is to be done, but how it is to be done and the exact time allowed for doing it.”

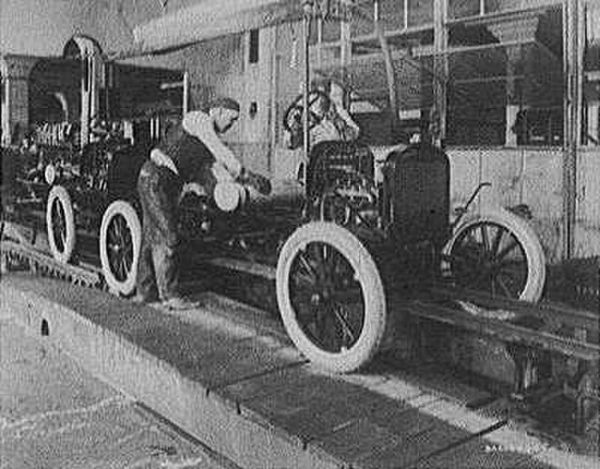

Henry Ford’s “progressive production” system — implemented in his auto factories after 1910 — took Taylor’s “scientific management” a step further — changing the physical machinery and layout of production as a way to re-organize the labor process. Ford engineers put to use Taylor’s method of time and motion studies, to analyze the time each task might take. For example, pistons were initially assembled by a single worker from rods and piston heads through a series of steps. When the engineers timed the various steps, they discovered that workers spent 4 hours of a 9-hour day just moving about. Engineers re-organized piston assembly with workers in stationary locations and the work divided into simple steps done by separate workers. Ford’s work reorganization consciously aimed to create simple, de-skilled jobs that could be done by people who lacked the traditional craft skills of the former skilled assemblers and machinists. The re-organization also used physical equipment — such as assembly lines — to impose a very intense pace of work.

This tendency to degrade work falls out of the logic of capitalist production. As Harry Braverman wrote in Labor and Monopoly Capital:

The capitalist mode of production systematically destroys all-around skills where they exist, and brings into being skills and occupations that correspond to its needs, Technical capacities are henceforth distributed on a strict “need to know” basis … Every step in the labor process is divorced, so far as possible, from special knowledge and training and reduced to simple labor.

Because of the inherent tendency of capitalism to develop technology in ways that intensify work, monitor and control workers, and subject workers and working-class communities to damaging chemical exposures and emissions, capitalist technological development is not “class-neutral.”

The focus of control of technology, work planning, product development, and marketing in the bureaucratic control class (managers and top professionals like corporate lawyers and industrial engineers) in the 20th century has led to a process of vast bureaucratic bloat through an apparatus of control apart from the workers who do the work. For example, managers were only 3 percent of the workforce around 1900 but are now more than 15 percent. Because the bureaucratic control class is an oppressor class, this is another way that capitalist technological development is not class-neutral.

Although the “scientific management” label is no longer in fashion, contemporary “lean production” methods (such as Just In Time truck delivery to stores or factories) and computerized monitoring and work control are simply the latest twist in the application of “scientific management” principles. In lean production ideology, any amount of time workers have for themselves at work — any moment they are not actively doing work that will generate income for the firm — is regarded as “waste.” Since the introduction of lean production techniques in the 1980s, firms have crafted an intensified work regime through tactics designed to squeeze out as much of this “waste” as possible, driving a more intense pace of work. A study of work intensification (reported by Kim Moody in On New Terrain) found that:

- The number of breaks during the weekday fell by 30 percent between the 1980s and early 2000s for men, and 34 percent for women.

- The total time spent in breaks declined by 20 percent for men and 27 percent for women

- Total break time declined from 13 percent of the workday in the ‘80s to 8 percent in the early 2000s.

These techniques have enabled capitalists to gain 24 minutes of additional work effort in a typical eight-hour day — without any additional compensation to workers.

We can see this idea in practice in the way Amazon runs its warehouses. Amazon employs about 29 percent of all warehouse workers in the USA and is an industry leader in techniques of labor control with extensive use of Artificial Intelligence and algorithms to track and manage workers. When warehouse workers pick items to make up a customer’s order, they use hand-held bar-code scanners. These also tie into the company’s tracking software. They try to detect any time the worker is not acting on a work task. They call this “Time Off Task.” They use competitive lists — a practice called “stack ranking” — of who is most “off task” during the course of the day to pressure people to work faster. Time off task can lead to reprimands or firing. If a worker claims they went to the bathroom, the company uses its pervasive video surveillance to see if the worker’s claim can be verified.

Any time spent socializing or talking with other workers is regarded as “Time Off Task.” Thus the constant surveillance and pressure to avoid breaks and talking to other workers is also an anti-union tactic. Unions develop out of the social connections of people in the same workplace, and their daily interactions which helps to develop a sense of community. Forcing isolation and avoiding socializing on the job with others is a way to suppress this development of bonds among workers.

According to a recent survey of Amazon warehouse workers, 41 percent feel pressured to work faster. A similar percentage report being injured. Amazon has the highest self-reported injury rate of warehouse employers. Injury, exhaustion and burnout are endemic among Amazon warehouse workers. A large majority (69 percent) say they have had to take unpaid time off due to pain or exhaustion from work. The warehouse industry has a high self-reported annual injury rate (5.5 per 100 workers) but Amazon’s self-reported rate is 6.7. (The economy-wide average annual injury rate is 2.7 per 100 workers annually.) Workers are afraid of taking water or bathroom breaks lest their “Time Off Task” rate is too high.

The use of AI and tracking algorithms is as much a form of machine-pacing as Henry Ford’s assembly line. And these tactics fall directly out of the logic of capitalist technological development — the search for higher output per worker hour.

The Capitalist Engine of Environmental Devastation

Capitalism has an inherent tendency to develop technology in ways that degrade work, are destructive to worker health and freedom, and also has an inherent tendency to degrade the environment.

To account for the system’s tendency to environmental devastation, critics often point to two aspects of the dynamics of capitalism. First, socialist environmentalists — including both Marxists and anarchists — often point to the system’s relentless drive for growth. Competition forces firms to do this. Capitalist firms seek profit to build up the scope of their operation, to develop new markets, and hire more experts and managers. If they can’t do this, more muscular firms will drive them from the field. Thus there is a tendency to growth of output to achieve higher revenue. Creating new products has often been part of the strategy to grow the firm, as in the vast growth in the markets for automobiles and appliances during the past century. Thus in practice capitalism generates persistent expansion in the production of commodities for sale. This leads a particular group of critics — the “degrowthers” — to argue that growth is the basis of the environmental crisis. “Infinite growth on a finite planet is absurd,” they will say. This has a certain plausibility to it.

Since World War 2 there has been a vast growth in the burning of fossil fuels and a massive expansion in the production of plastics by the petrochemical industry. This is sometimes called the “great acceleration.” And the rise in global temperature since 1950 goes hand in hand with increases in heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere.

The three main heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere are carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. Methane has various sources such as leaky gas fields and animal feedlots. Although the natural gas industry has often touted methane as a “cleaner” fuel than coal for electricity generation, gas-powered electricity generation contributes just as much to global warming as coal power plants due to leaks of methane from gas fields. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), current levels of methane in the atmosphere are 160 percent higher than in the late 1800s. According to a recent report, “Just four of Europe’s gas-fired power plants have a retirement plan and new projects will increase the continent’s gas generation capacity by 27%, according to analysis from the campaign group Beyond Fossil Fuels.”

“It’s really significant to see the pace of the increase over the first four months of this year [2024], which is also a record,” said Ralph Keeling, director of the CO2 Program at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “We aren’t just breaking records in CO2 concentrations, but also the record in how fast it is rising…The rate of rise will almost certainly come down, but it is still rising and in order to stabilize the climate, you need CO2 level to be falling,” Keeling said. “Clearly, that isn’t happening.”

Even though I agree that the growth dynamic has been a major factor in the vast ramp up of fossil fuel burning and plastics pollution, I don’t think growth is the underlying source or cause of the global warming crisis or the system’s tendency to environmental devastation. I think the source is a another feature of the system’s dynamics. An essential part of the profit drive is the constant effort of firms to reduce their expenses per unit of output. This is itself the basis for both the degradation of nature and the degradation of work over time. Capitalism has used all sorts of tactics to extract materials from nature at the lowest price, from avoiding costs of repairing environmental damage from mining and smelting to land grabs against indigenous populations. Unsustainable extractivism — such as over-fishing in the oceans or clear-cutting of forests — avoids the social cost of ensuring the future of the resource. Capitalism also uses nature as a free dumping ground for its wastes. Nancy Fraser (in Cannibal Capitalism) describes the way this combination of profit drive and cost-shifting plays out:

“Capital commands accumulation without end. The effect is to incentivize owners bent on maximizing profits to commandeer ‘nature’s gifts’ as cheaply as possible, if not wholly gratis, while also absolving them of any obligation to replenish what they take and repair what they damage.”

Capitalism minimizes expenses by avoiding liability for the damaging effects of its emissions and environmentally destructive products. Cost-shifting is a pervasive feature of capitalism. If an electric power utility burns coal in a power plant, the emissions may damage the respiratory systems of thousands of people downwind, and also contributes to global warming. Indeed, according to a recent study, coal-fired power plants have killed at least 460,000 Americans in the past two decades, causing twice as many premature deaths than previously thought.

Thus I think the more basic explanation of capitalist degradation of nature lies in the system’s pervasive and inherent tendency to cost-shifting. Nonetheless, the degrowthers have a point: Growth does play a role because capitalism’s expansionist drive amplifies the effects of cost-shifting.

Negative externalities are a pervasive feature of capitalism. Just as a power firm burning coal pays nothing for the damages from its emissions and its contribution to global warming, the natural gas industry pays nothing for the way leaks of organic volatile compounds have damaging effects on the health humans and other animals in rural areas nor do they pay for the contribution to global warming from the major methane gas leaks of gas fields. Although emissions from burning natural gas in a power plant contribute less carbon dioxide than a coal power plant, the methane leaks at gas fields make natural gas just as powerful a source of global heating as burning of coal. Firms that make profits from building cars and trucks that burn gasoline or diesel also pay nothing for the vast buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere contributed by the vast expansion in use of motor vehicles since World War 2.

Thus we can say the global warming crisis has its root cause in the way firms minimize expenses through dumping wastes into nature — in all phases of economic activity, from extraction of resources to production processes and the damaging effects of products designed by the capitalist firms — such as exhaust emissions and carbon dioxide from the vehicles produced by the capitalist vehicle industry.

You’ll notice here that I’m focusing on how environmental devastation is rooted in production — not consumption. Some environmentalists try to suggest that we should understand the global warming problem by looking at the choices of consumers. They use ideas like a person’s “carbon footprint” to focus on personal consumption. But consumers of electric power don’t have control over the decisions of power firms about the methods of electricity generation, or what technology firms will rely on to move freight around in the global supply chains.

A useful concept here is throughput. The throughput of production consists of two things: (a) All the material extracted from nature for the production process (minerals from mines, wood from forests, fish from the sea), and (b) all the damaging emissions (“negative externalities”) from the production process.

With the concept of throughput, we can define a concept of ecological efficiency. If a production process is changed in ways that reduce the amount of damage from emissions (or amount of extracted resource) per unit of human benefit, then that change improves ecological efficiency. For example, replacing coal or gas-burning power plants with renewable sources such as solar or wind power increases the ecological efficiency of electricity production. Under social pressure and with government mandates and subsidies — and increasing market opportunities — there is a “green” capitalist sector who produce electric vehicles, batteries, and solar and wind power equipment. They do this because they can make money doing so. Meanwhile, many capitalist sectors drag their feet, and hold on to their sunk investments in fossil fuel technology.

And here is a basic structural problem of capitalism: It has no inherent tendency towards ecological efficiency. If nature is treated as a free dumping ground for wastes, there will be no tendency to minimize damaging emissions per unit of human benefit from production. They will also try to obtain needed materials from nature “on the cheap” — engaging in land grabs or avoiding clean-up costs.

A production system that could generate increasing ecological efficiency would tend towards reductions in pollution and damages of resource extraction. This would require a non-market type of eco-socialist economy where worker-controlled industries are not profit-driven and mass participation in institutions of popular power is able to hold production organizations socially accountable — required to systematically internalize their environmental costs. Production organizations would then have an incentive to develop new technical methods of production to reduce material throughput and damaging emissions. An economy of that sort would have a tendency towards increasing ecological efficiency of production. With a dynamic towards greater ecological efficiency, growth of output for human benefit could occur without increasing ecological damage. This would make “green growth” a real possibility.

Historical Materialism

Among socialists in the early 20th century, productivism found support in a particular interpretation of Marx’s theory of historical change — “historical materialism.” Marx’s theory is based on his hypothesis about the way a society is built around its “mode of production” — the way humans organize the production of goods from the resources and capacities of nature. In Marx’s hypothesis, a mode of production has two components. The “social relations of production” are the way groups have social power in social production, such as the class structure and competitive dynamics of the capitalist setup. The second structural component is the “forces of production” that have been developed in that society. The forces of production include both the humans who work in production and their skills and know-how as well as the land, buildings and equipment they work with. In other words, everything included under “technology” as I defined it.

The theory of historical materialism can be interpreted in different ways. In the first half of the 20th century both social-democratic and Leninist Marxists tended to identify “development of the productive forces” with technological “progress.” The idea is that technological development under capitalism is “progressive” because the capitalist drive to increase labor productivity builds a potential for improved living standards. The emphasis on the “primacy of the development of the productive forces” was especially attractive to Marxist-Leninist intellectuals in less developed countries.

G.A. Cohen’s book Marx’s Theory of History: A Defense provides perhaps the clearest and most rigorous defense of this productivist version of historical materialism. This version of the theory is committed to the idea of the primacy of development of the productive forces over social relations of production in history. The idea is that a particular class structure (“social relations of production”) may come to block (“fetter”) further technological progress. And this is then seen as the cause of a shift to a new mode of production. Thus the tendency towards technological advance is regarded as a trans-historical force that can blow up inadequate systems of “social relations of production.” This is essentially a form of technological determinism. The independent tendency towards technological progress is supposed to explain the existence of capitalism.

Strange, then, that Marx doesn’t refer to technological development when he provides an historical sketch of the rise of capitalism (as in Capital, Vol I). Marx refers to European trade and colonial expansion and the wealth this brought to home country merchants. Merchants then used this wealth to set up manufacturing — such as the early system of contracting with artisans. After the nobility in Britain exhausted themselves in dynastic wars, wealthy merchants bought up the estates. Of course they brought their commercial orientation to managing the properties. With the rise in the demand for wool on the continent in the 1500s, this presented an opportunity for the land owners. They could increase their income by expelling the peasant subsistence farmers and setting up large-scale sheep herding. And the peasantry expelled from the land under the enclosures movement then became the basis of a proletarian class — initially hired in agricultural labor. But the techniques used to produce wool were just the traditional sheep raising methods. Technology plays no role in the story sketched by Marx. Of course, once the capitalist mode of production was established, its characteristic structural features would generate the dynamic tendency to constant technological change.

Cohen’s theory must assume that the tendency to technological advance is independent of the “social relations of production,” that is, the system of class control over human beings in production. But my earlier discussion of how capitalism develops technology to control workers — from Taylor’s speedup schemes to Ford’s “progressive production” to the latest forms of lean production as in Amazon warehouses — shows this is clearly false. There is an internal relation between the capitalist methods of technological development and labor control, work degradation and adverse impacts on worker health.

Cohen tries to get around this problem by arguing that management labor control techniques are separate from management’s technical know-how. He says the labor control techniques are “work relations” which are part of the “social relations of production.” But what defines the distinction? Cohen suggests that only those aspects of management practice that are necessary for enhancing “efficiency of production” are part of the technology. But this is not a plausible claim. In capitalism “improved efficiency” is typically understood as reducing the expense per unit of output.

Amazon’s tight labor control is used to minimize worker hours per unit of output — and thus is a contribution to efficiency. Ford’s progressive production techniques enabled Ford to reduce the price of the Model-T from $800 in 1908 to $250 in 1924. Cohen must claim that all the video surveillance and algorithmic managerial techniques and computer programs for labor control in Amazon warehouses are not part of the technology of capitalist production. But if there is a the sharp separation of technology from the social relations of production, Cohen’s theory is incoherent.

Moreover, Cohen doesn’t really offer a plausible account of causal processes in history that would explain the independent tendency to technological progress. His theory assumes a kind of teleology in history — towards continuous technological “progress.” In reality the tendency to constant technological change has only really been a feature of the capitalist era — driven by the specific competitive dynamics of capitalism. And thus is explained by the “social relations of production.” This constant technological change was not present in previous types of social arrangement. In pre-capitalist societies technical improvements tended to happen only occasionally as one-offs. Moreover, it would be rather implausible to suppose that the peasantry and artisans of the middle ages would be less likely to improve productivity without the coercive rule and rent extractions of the feudal barons. Feudalism was based on coercive military power, not its ability to support productivity.

To defend the idea of teleology in history, Cohen makes an analogy with evolutionary theory. Evolution is able to explain functionality of biological structures and processes through the theory of natural selection which eliminates any cosmic designer in favor of physical processes. For example, eyes have the function of providing sight. The meaning of “function” is cashed out in terms of the way having sight explains survival of an animal species due to sight. The contribution of this activity to animal survival explains why the eye structures are reproduced down through the generations. Biological theory provides a back story to explain how this works by identifying the causal mechanisms such as random mutation and DNA copying. Cohen does not have a plausible account of the causal mechanisms that would explain a trans-historical tendency to development of the productive forces.

A fundamental defect of this productivist version of historical materialism is that it reverses cause and effect. In reality, the capitalist social relations of production largely shape the form of technological development that takes place within the capitalist regime. The persistent and inherent cost-shifting tendency in capitalism is a structural feature that shapes technological decisions by capitalist firms. Thus capitalism has an inherent tendency to degrade work, damage worker health, and degrade the environment. This is why “development of the productive forces” under capitalism is not class neutral or socially neutral.

Just as the development of the productive forces is supposed to explain why we have the economic structure we do, on Cohen’s theory, the “social relations of production” are supposed to explain the features of the legal and governmental system. The idea is that the state institutions survive over time because of their role in sustaining and protecting the capitalist accumulation game. But this assumes the class system is independent of the state. In reality, class oppression is inherent to the state itself. We can see this in the subordination of workers in the public sector to a top-down corporate-style managerial bureaucracy — teachers, public transit workers, road maintenance workers, and so on. Moreover, coercive public institutions were also implicated in the emergence and creation of capitalist power — a point emphasized in social anarchist theory.

Nonetheless, there are certain useful insights in Marx’s “mode of production” hypothesis. The way humanity makes its living through modification of nature in production processes does seem very fundamental to human societies. Moreover, the way power over social production is structured is essential to explaining the course of events in capitalist society.

In reality there are multiple inherent structural conflicts in capitalism. There can be conflicts between technological development and entrenched class power but these conflicts are only one fault line in the society. There is the fundamental conflict between the subordination and exploitation of workers and the direct resistance and struggle developed by workers and their organizations to fight back. The working class is itself the primary productive force. Workers have the capacity to shut production down in strikes and plant occupations and engage in other forms of resistance. They also have the potential to build their own organizations — from unions to worker committees and tenant organizations —and thus build their own sense of power and potential to change the system. Indeed, the working class has the potential to build a movement that could expropriate the capitalists and re-organize production through democratic worker self-management of the industries. Despite Marx’s emphasis on worker self-activity and the development of class consciousness through struggle, class struggle is largely “disappeared” in Cohen’s technological determinist reading of historical materialism.

And there are other structural fault lines such as around capitalism’s tendency to exploit caring work through shifting of costs to unpaid or poorly paid care workers (especially women). And today of course capital’s inherent tendency to degrade nature through cost-shifting has reached crisis proportions — threatening the very human civilization capitalism is based on.

The Green Syndicalist Alternative

What we are likely to see going forward is a growing convergence between the struggle over capitalism’s tendency to environmental devastation and the struggle of workers against boss power and exploitation in the capitalist economy. The growing trend towards green unionism is evidence for this convergence. This is where workers use their organized strength to fight back against environmentally damaging practices of their employers. The struggle of truck drivers in the USA against the dire effects of heat in truck vans, the support of environmentalists for the recent struggle of German transit workers for greater support to public transit, the demand of the United Electrical Workers union in their 2022 strike at the Erie locomotive workers for production of green locomotives, the 2020 effort of the union at Rolls Royce in Britain for production of low-carbon products, and the recent strike of West African fish industry workers on Spanish and French fleets against over-fishing are all examples of the trend to green unionism.

Green syndicalism is an anti-productivist alternative that builds on this potential for direct worker struggle — and worker and community alliances — to be a force against the environmentally destructive tendency in capitalism. The goal of green syndicalism is a self-managed form of eco-socialism where workers take over the democratic self-management of the industries they work in. The proposal is to build a horizontally federated system of production based on a distributed, democratic system of planning by worker and community organizations. Direct worker power to cooperatively self-manage whole industries generates an entirely different approach to technological development compared to the capitalist regime. Workers would gain control over this process and could ensure that job organization and technical methods of production enhance worker health and safety, build worker skills, and work to integrate the planning and decision-making activity with the actual doing of the work.

This shift would also enable the workforce to capture improvements in labor productivity for reductions in the workweek and ensure that self-managing work experience is shared out among all who are available for work.

With accountability to the broader community in a socialized production system, workers and communities can also strive to reduce damaging emissions per unit of output, and work to lessen the extractivist load on the planet, for example, through enhanced systems of recycling. A reduction in damaging emissions and material throughput per unit of human benefit makes growth in human benefit compatible with environmental sustainability.