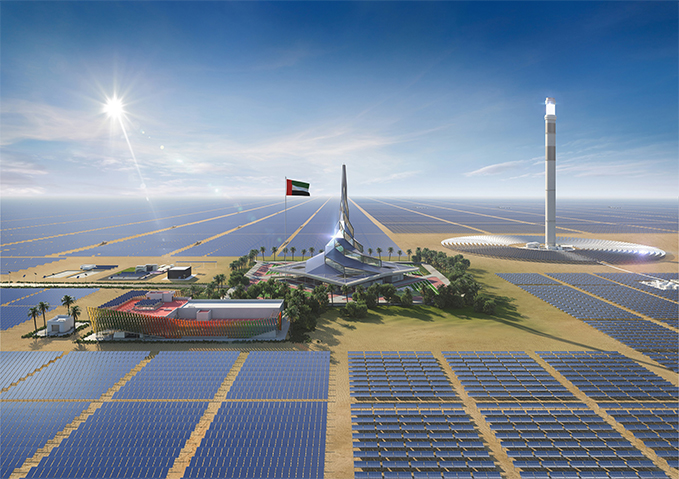

Far from the skyscrapers of urban Dubai, the solar panels of Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park shine in the seemingly pristine desert.

Stretching over 30 square miles, this spectacular solar installation offers the image of green energy production that the UAE wants to showcase to the world. Writing in Time magazine last November, journalist Justin Worland described the scene from a helicopter tour arranged by Emirati officials. From one window, he could see a vista of desert sand dunes, from the other, “a science fiction-like array of solar panels, covering an area larger than Manhattan.”[1]

In neighboring Abu Dhabi, Emirati leaders have touted a similar megaproject, the Noor Abu Dhabi park, as the “world’s largest single-site solar power plant.”[2] And hypermodern images of solar power bombarded anyone who attended COP28, the United Nations climate talks controversially held in Dubai in 2023.

Sparkling solar technologies figure prominently in the UAE’s official efforts to advertise its sustainability credentials and affirm its commitment to tackling climate change. The UAE’s National Energy Strategy 2050 promises to triple its minuscule 4.2 percent renewable energy capacity by 2050, and solar projects are a large focus of this plan.

But although large-scale solar energy projects may seem like a move toward a greener energy future, celebratory images of solar power in the desert obscure the problems of utility-scale parks. From California to China, large-scale solar projects stress water supplies, divert resources from local communities and threaten local habitats. Energy megaprojects across the Middle East and Northern Africa offer some of the most poignant lessons about why desert solar is a spectacular fiction rather than a spectacular future.

Wastelanding the Desert

The most impressive solar photos are often set in the desert, which functions as a synecdoche for today’s climate crisis. A patch of parched soil has become one the most cliched icons of climate change and environmental collapse, evoking fears of a warming planet, water scarcity and future challenges of securing food in a changing environment. But the desert as an icon of a looming climate apocalypse is not new. The desert has long circulated as a trope in European and US imaginaries and is not understood in its full human and ecological complexity.

Reducing the desert to a barren and lifeless place is part of a process that historian Traci Voyles has called “wastelanding.”[3] Symbolically relabeling certain places as a waste rather than inherently valuable makes it easier to justify violence to physical landscapes and transforms the wasteland into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Wasteland stories also depopulate arid landscapes, erasing the human and nonhuman life that call the desert home.

Symbolically relabeling certain places as a waste rather than inherently valuable makes it easier to justify violence to physical landscapes and transforms the wasteland into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

When solar panels are applied to the apocalyptic scene of a parched desert landscape, the wasteland image is suddenly transformed into a vision of prosperity and optimism. The message of the iconic desert solar image is both persistent and consistent: a brilliant and inarguably good solution to the climate crisis.

Yet, the solar-as-salvation message has several flaws. Arid environments pose many challenges for solar operations. Dust and sandstorms mean that utility-scale parks, like those in the Dubai desert, require substantial water inputs to clean solar panels that regularly grow coated with dust. In the Arabian Peninsula, this process usually involves the use of desalinated seawater, which itself has a huge carbon footprint as it is powered by burning oil or natural gas. Utility-scale solar parks also require the construction of new transmission lines and road networks, not to mention regular technology replacements due to the degrading effects of extreme temperatures.

Another notable feature of the solar-as-salvation images is they never include humans: The iconic cracked desert ground is always depopulated ground. But, of course, deserts are not empty, and solar projects can adversely impact local communities and their livelihoods. For example, in Morocco, solar power megaprojects at the Noor-Ouarzazate complex have involved massive land grabs and threatened local water supplies. The Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy initially promised the project would create thousands of jobs for surrounding communities. But this promise has remained unfulfilled. Instead, local residents find themselves struggling with economic insecurity, severe drought, fires and the near collapse of traditional oasis farming—all while the solar power plant draws down their precious water resources.

The neat and tidy image of solar panels in the desert also hides the question of what—and who—the solar energy is for. In the case of Morocco, the Noor solar megaproject is largely hoped to produce energy for export to Europe. Moroccan elites have disregarded local concerns and instead leveraged the European Union’s desperation for green energy to position Morocco as a vital partner in the EU’s energy transition. As a result, large-scale solar projects can deepen authoritarianism by concentrating more financial and political capital into the hands of government leaders at the expense of local communities.

Similar processes of authoritarian energy transitions are happening across the region.

Desert Solar as Extractivism

In 2015, the BBC posed a question: “Should we solar panel the Sahara desert?” Several researchers, three from Europe and one from Africa, weighed in on whether it was a viable “solution to climate change.”[4] In 2019, a researcher based in Britain asked the same question in a piece for The Conversation: “Should we turn the Sahara Desert into a huge solar farm?”[5]

These questions serve as a shorthand for justifying an extractive energy relationship between Europe and Africa through solar power. They imply a “we”—residents of European countries—that possess the capital and expertise to export solar technology but simply need the energy that Africa’s largest desert can provide. They also imply that since Africans are not tapping the energy potential of the Sahara Desert, they must not need it.

In this extractive vision, deserts in the Middle East and Northern Africa play the same role for solar power as they do for oil: The deserts are barren and unproductive but hide extravagant wealth beneath their sands—wealth that is only accessible if subjected to the right technological tools.

The idea of sending solar power from deserts in the Middle East and North Africa to Europe is not new. The Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy Cooperation “Desertec” (first proposed in 2003 by a consortium of mostly European power companies) is perhaps the best-known example in recent years. As Algerian activist and public intellectual Hamza Hamouchene has argued, these European-facing schemes are built on a distinctly neo-colonial logic of extractivism. In this extractive vision, deserts in the Middle East and Northern Africa play the same role for solar power as they do for oil: The deserts are barren and unproductive but hide extravagant wealth beneath their sands—wealth that is only accessible if subjected to the right technological tools.

In the fossil fuel era, the celebrated technologies were the drills and rigs that could extract oil from underground. In the post-oil era, the celebrated technologies are the gleaming photovoltaic panels and concentrated solar power parabolic troughs and towers. Once again, the Global North is positioning itself as the bearer of technology. Now, they have the added moral sheen of good-willed environmentalists on a mission to stop a climate crisis—one that they created—by importing energy from elsewhere to sustain their own unsustainable energy demands. The depoliticized image of sparkling solar panels in the desert is a key tool in such moral posturing.

Europeans aren’t the only foreigners interested in the solar potential of the Middle East and Northern Africa. Political and economic elites from the Arabian Peninsula have also been active in the sector. As opposed to their European counterparts, the Gulf actors are less interested in importing renewable energy for their own consumption. They are instead aiming to green their oil money and extract the financial rewards of owning the infrastructure of the renewable energy transition. In part, Gulf leaders recognize the physical limits of renewable energy projects in the Arabian Peninsula, but the increasing trend in the region is for Gulf-based companies (state-owned, parastatal and private) to invest overseas instead of at home. Saudi state-backed ACWA power has assets across the Gulf, the broader Middle East and parts of Africa.

Abu Dhabi’s Masdar Future Energy, a subsidiary of its Mubadala sovereign wealth fund, now boasts a remarkable portfolio of renewable energy investments well beyond its early reach in the Middle East. Private Emirati elites like the Abu Dhabi-based Al Nowais family’s AMEA Power are also investing in the industry. Since receiving significant new funding from Japan’s SoftBank in 2023, the company has become one of Africa’s fastest-growing renewable energy developers, with projects across the entire continent.

In the Gulf as in Europe, supporting spectacular sustainability projects gives moral license to leaders who perpetuate the fossil energy system that they still wholly rely upon. But similar to their European counterparts, they also seek the symbolic capital of high-profile solar projects, allowing them to globally broadcast their supposed climate virtues and financially profit from the post-oil energy transition. In the Gulf as in Europe, supporting spectacular sustainability projects gives moral license to leaders who perpetuate the fossil energy system that they still wholly rely upon.[6]

The strategic use of solar spectacles is evident to differing degrees across the Arabian Peninsula. In some cases, these projects are announced solely to grab headlines and then scrapped when the media moves on. In March 2018, for example, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman signed a $200 billion deal with the Japanese investment giant SoftBank to create the world’s largest solar power project. Loudly hailed across the global media landscape, Prince Mohammed told the press: “It’s a huge step in human history. It’s bold, risky and we hope we succeed.”[7] The plan, however, was canceled only six months later—a development that was ignored by the same international outlets that had breathlessly celebrated it.

Beyond Solar Fetishism

The fanciful images of desert solar are just that: fancies. But they can be dangerous ones.

As Ozzie Zehner argues, a fundamental challenge of sustainability spectacles, like the massive solar farms in the desert, is that they are presented as inarguably good and flawless. More than a decade after his 2012 book Green Illusions was published, people still ignore “the limitations of alternative energy as we drop to our knees at the foot of the clean energy spectacle, gasping in rapture.”[8]

In the frenzied rush to promote the renewable energy transition, few stop to ask what the energy is actually being used for and whether it is even necessary. The colonial idea of solar-paneling the Sahara for Europe’s benefit is only deemed necessary because European leaders are unwilling to countenance a shift away from energy-intensive industry and capitalist systems of endless production.

Some groups have proposed alternative approaches, such as the “degrowth” movement that is gathering momentum in Europe. For these advocates, climate change demands a move away from energy-intensive capitalism and a wholesale reorganization of modern economies to scale down industry, production and consumption. In the Middle East and North Africa, by contrast, anti-growth climate solutions are rarely broached. But as the degrowth advocates argue, a major shift in economic values is essential for any meaningful impact on the climate crisis since infinite growth cannot be sustained on today’s warming planet.

A degrowth approach would challenge the symbolic economy around renewable energy—particularly desert solar. From a perspective that critiques rather than celebrates capitalist expansion, desert solar would instead be recognized for what it is: A spectacle that many people and companies are now manipulating to excuse their energy-intensive lifestyles, while wastelanding socially and ecologically precious desert landscapes around the world.

For these advocates, climate change demands a move away from energy-intensive capitalism and a wholesale reorganization of modern economies to scale down industry, production and consumption.But more than a simple issue of physical geography, the renewable energy transition is fundamentally tied to questions of political geography: Who gets what, when, where and how? Solar power may be good for some people and in some contexts—but not everywhere and for everyone. Whatever the renewable energy source may be, better than fossil fuels does not automatically equal good.

Today’s environmental challenges extend beyond the abstract numbers of greenhouse gas emissions and rising temperatures. Communities in deserts across the world understand the need to conserve water, grow food, protect cultural sites and livelihoods and keep ecosystems intact. Yet their voices are drowned out by the deluge of solar spectacles that draw critical attention away from key political decisions about how to imagine just futures in the desert. For those who see the desert as, not a wasteland, but home, desert solar is a spectacular fiction, not a spectacular future.

Endnotes

[1] Justin Worland, “What Happens When You Put a Fossil Fuel Exec in Charge of Solving Climate Change,” Time Magazine, November 15, 2023.

[2] “World’s largest single-site solar power plant in Abu Dhabi,” Economic Times, January 21, 2021.

[3] Traci Brynne Voyles, Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

[4] BBC News, “Should we solar panel the Sahara desert?” December 30, 2015.

[5] The Conversation, “Should we turn the Sahara Desert into a huge solar farm?” April 24, 2019.

[6] Natalie Koch, “Scientific Nationalism and Museums of the Future in Germany and the UAE,” Political Geography 113 (2024): p. 103144.

[7] Quoted in Frank Kane , “Saudi solar energy comes of age at the stroke of midnight in New York,” Arab News, March 29, 2018.

[8] Ozzie Zehner, Green Illusions The Dirty Secrets of Clean Energy and the Future of Environmentalism (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), p. 149.