After six months of political wrangling with the European Parliament, the new von der Leyen Commission started its work on 1 December 2024.

Is the European Commission the “government,” the executive, of the European Union (EU)? Not really because the Commission, and not the Parliament, has the right of legislative initiative. European legislation arises because the Commission launches a legislative proposal. If it is then approved, possibly amended, by a majority in Parliament as well as by the Council (consisting of ministers of the member states), it becomes European law.

But at any moment, e.g., when the amending goes in the ‘wrong’ direction, the Commission may withdraw its proposal. There is consequently no chance that a European law will pass if it is not judged acceptable by a non-elected Commission. Another dubious practice is the ‘trilogues’. When Parliament and Council do not agree in their judgment of a Commission proposal, a small group consisting of leaders of the Parliament and a representation of the Commission and the Council meet behind closed doors and usually get a compromise. This then directs the plenary vote in Parliament. The quid pro quos agreed behind the closed doors remain a secret, as there are no minutes of the trilogues.

The Obscure Regulatory Scrutiny Board

An even more obscure body, totally unknown by the public, is the ‘Regulatory Scrutiny Board’, nine individuals who do the ‘quality control’ of Commission proposals before they are presented to Parliament and Council. If their advice is negative, the Commission revises the proposal. The Regulatory Scrutiny Board is “totally independent” and “acts independently from the policy-making departments” of the EU; strange enough, five of the nine members are high ranking officers from these departments. And among the four ‘outsiders’, they have links to national governments, businesses, consultancy, OECD, etc.

The German politician Ursula von der Leyen was appointed at the end of June 2024 as Commission President for another five-year term after secret political negotiations among heads of government belonging to the three so-called ‘pro-European’ political families. These are often referred to as ‘the Platform’ because they invariably ensure a majority in Parliament. They are the conservative European People’s Party (EPP) to which von der Leyen belongs, the “Socialists and Democrats” (S&D), and the liberal group “Renew.” Also, the other top job – the ‘High Representative of the Union for Foreign and Security Policy’ – was awarded to Estonia’s prime minister, Kaja Kallas. She is known for her sharp dislike of Russia, China, Iran, and Venezuela.

For the other 25 commissioners, the remaining member states are in charge, each government determining in an unspecified manner the ‘candidate for Brussels’. The outcome depends on the relations between national coalition partners but is not related to European elections. Thus, the body that has a monopoly on legislative initiative in the EU is actually the result of coincidences and national party-political considerations: so much for the democratic legitimacy of the Commission. For example, it is due to such coincidences that in the new Commission, 15 of the 27 (55%) commissioners belong to the EPP, which holds 26% of the seats in Parliament. Liberal Renew cannot complain either: five commissioners (18%) for 11% of parliamentary seats. Bad luck for Greens: no government sent a Green candidate to Brussels, even though they make up 7% of Parliament.

The Commission President Dictates the Programme

If we consider the Commission as the ‘European government’, one would expect coalition talks to be held in order to arrive at a government programme. But that, too, is different in the EU. The ‘programme’ was announced before the Parliament on 18 July: Political guidelines for the next European Commission, signed: Ursula von der Leyen. Two months later, after all member states had announced their future commissioners, she could present her cast, a name on each portfolio, accompanied by a mission letter, stating what the Commission president expects. There were some surprises here too: a ‘defence commissioner’ had never existed before, defence not being a power of the EU, while the traditional commissioner in charge of employment and social policy had disappeared.

To see in von der Leyen’s way to proceed as a kind of one-woman regime would surely be a misunderstanding. It is unthinkable that ‘Brussels’ could pursue its own policy against the will of the (big) member states. A sentence from von der Leyen’s guidelines actually admits this: “The priorities set out here draw on my consultations and on the common ideas discussed with the democratic forces in the European Parliament, and also on the European Council’s Strategic Agenda for 2024-2029.” The legitimacy of the ‘programme’ is thus that it is simply distilled from what, according to the president, the democratic forces demand.

A Competitive Economy Prepared for War

The first place in the 2024 guidelines is devoted to economic competitiveness rather than the European Green Deal as in 2019. If we do not want to fall hopelessly behind the Americans and the Chinese, it must be made easier for companies to do business, thus the new top priority. No wonder then that the day after the inauguration of von der Leyen II, the Council of Ministers was already meeting to see which legislation needs to be pruned in order to give ‘breathing space’ to our companies. Two regulations in particular are a thorn in the side of entrepreneurs, as recently revealed by a wish list of French, German, and Italian business organisations: the so-called CSDD and CSRD directive. These expect (large) companies to report a minimum on their sustainability and respect for human rights; alas, this is unwanted ballast for a competitive economy. However, it is rather dubious that the economic balloon will fly higher with this ballast removed.

It is also unclear how the Union would be able to mobilise €800-billion to stir up the European economy, as judged necessary by the former president of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi, who prepared a report on European competitiveness. Member states are more used to the beggar-thy-neighbour principle than investing in common European measures.

The second chapter of the guidelines heralds a “new era for European defence and security.” Now that “Ukraine is fighting for our freedom, democracy and our values,” the European Defence Union needs to be sped-up, and for that a defence commissioner (Andrius Kubilius) was appointed for the first time. He demands at least €500-billion over ten years for investment in defence, to support Ukraine, and to shelter the EU against Russia. Where should the money come from? Some want to issue common European debt (‘eurobonds’), but this goes against the ‘frugal’ member states, which oppose a ‘debt union’.

Other solutions are in the making. There are billions of euros destined for supporting underdeveloped regions (‘cohesion funds’) but unused up to now; a change of the rules will make them accessible for military purposes. Even more ‘witty’ is the recent decision that the defence industry is to be labeled sustainable and green because of its “significant efforts to transition to less energy-intensive and carbon-emitting manufacturing processes”; consequently, it shall have access to green funds, cheap loans, etc.

But the security of the Europeans is not only threatened by a bellicose Putin but also by ‘pressures at our borders’, as von der Leyen’s Political guidelines put it. The ill-famed Border and Coast Guard Agency, FRONTEX, involved in several cases of illegal pushbacks, will be expanded from 10,000 to 30,000 guards, equipped with state-of-the art technology. New plans are in the pipeline to develop more ‘strategic relations’ with African governments in order to prevent migrants from heading for the EU and to take back nationals who have been labeled illegal. The already existing deals with Libya, Egypt, and Tunisia show their often criminal nature. It is also clear that the much-lauded rule of law may be broken when it involves protecting the Fortress against intruders. Poland recently decided to suspend the right to asylum, a decision that afterwards was approved by the Commission!

A Pinch of ‘Social Europe’, a Tablespoon of Peasant Romance

The third part of the guidelines is supposed to represent the social chapter. There is no shortage of ringing terms (Quality Jobs Roadmap, Anti-Poverty Strategy, Affordable Housing Plan, Gender Equality Strategy, etc.), but how do you budget for that when von der Leyen II is all about competition and more military spending? When the duties of the future commissioners were announced, the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) had protested against the removal of the traditional commission post in charge of employment and social policy. These responsibilities were now part of Commissioner Roxana Mînzatu’s role, in charge of the mishmash titled “People, Skills and Preparedness.” But on 27 November, in her speech to the Parliament asking for approval of her Commission, von der Leyen said, “I have heard your call. And I am happy to announce that social rights and quality jobs will become part of Roxana’s title.” Immediate reaction from ETUC was to distribute a press release titled “Unions win U-turn on quality jobs commissioner.” Or how a bureaucratically managed trade union confederation may be made happy with a dead sparrow…

In the fourth part of von der Leyen’s guidelines, with a lot of goodwill, one could see a climate and environment programme. It does begin with a goodwill declaration toward farmers, the vociferous protesters against too many European nitrate restrictions and other directives. Rest assured, farmers, “Farming is a core part of our European way of life!” as the guidelines say. But even farming does not escape the competitiveness imperative, which will be supported by the EU through investments in agricultural enterprises, in ‘our’ agri-food companies, and in small businesses. While the European Green Deal was mostly about carbon reduction, it is now more about adaptation and preparing for the worst.

Democracy, Rule of Law and Geopolitics

There is also a chapter on “protecting our democracy” and “upholding our values.” But here the old warning is appropriate: When the fox preaches, watch your geese! A “European democracy shield” is envisaged to counter information manipulation by foreign powers. Reference is made to the examples Viginum in France and the Swedish Psychological Defence Agency. The latter advises, for example, to look at the source of information and … consult official sources. The agency’s cooperation with the Swedish army, security services, and police is, of course, a conclusive guarantee of solid information… As for the “European values,” the “defence of the rule of law” is the central task. It is doubtful whether the announced intention of punishing breaches against the rule of law by withholding of European subsidies will change that, but it is even more doubtful whether linking payments from the European budget to the implementation of ‘reforms’ has anything to do with the rule of law. We see it rather as the abuse of power by a bureaucracy in its permanent attempt to further neoliberal policies.

Von der Leyen’s guidelines then talk about the fiercely cherished desire for the EU to become a geostrategic player of stature. All our existing assets must be used to this end. Enlarging the Union is a “geopolitical imperative” because it gives us more weight and influence in the global arena. The relationship with our neighbours must be considered strategically, which is why a commissioner for the Mediterranean is appointed. That the EU should “continue to participate in all diplomatic initiatives” to reach a solution to the ‘conflict’ in Gaza is a misplaced formulation, though, because the EU has not participated in any diplomatic initiative in that sense. Economic and trade policy should also be seen as a geostrategic tool; partnerships should ensure that critical ores and raw materials are available to us, and “we will be more ambitious in enforcing our trade agreements.” So far, von der Leyen is proud that after decades of negotiations the EU-Mercosur free trade agreement with countries from Latin America has been signed.

The guidelines conclude with vague descriptions of desired reforms: firstly, of the European treaties with a view to enlarging the Union, and secondly, of how the European budget will be used. Regarding the latter, we were hoping to get some clarification on reports that the Commission wants a totally different approach to the way member states receive money from the European budget. Until now, this has been done according to set criteria for various purposes: agricultural subsidies depending on the number, size, and nature of farms in a member state; ‘cohesion funds’ depending on the economic underdevelopment of certain regions; money for research and development depending on participation in certain programs; support for border protection depending on the situation; and so on. The Commission would have a fearsome stick to impose reforms on member states if the funds accruing to the various programs running in a member state were disbursed to the national government as a single sum, provided the reforms the Commission believes are necessary have been performed. Von der Leyen announces that she will formulate proposals on this in 2025, but she doesn’t show her cards at the moment.

Right-Wing Parliament, Right-Wing Commission, von der Leyen Firmly in the Saddle?

In the first half of November, hearings of the candidate-commissioners were held. Delegations of Parliament were supposed to test the suitability of candidates, their knowledge of the entrusted responsibility, etc. Media spoke of the ‘grilling’ of the candidates. But upon closer inspection, the members of parliament restricted their questions to the framework sketched by von der Leyen in her Political guidelines and the mission letter to each candidate. And the main political parties in Parliament were mainly concerned with the approval of ‘their’ candidates, rather than with the composition of a competent team of commissioners.

After the ‘grillings’, on 27 November, the European Parliament had to approve the Commission in its entirety. As expected, a majority was approved – the contrary would have been historically unprecedented. But it was the weakest of the century: 370 for, 282 against, 36 abstentions, with only 54% agreeing to the proposed Commission. All Commissions between 1995 and 2019 achieved between 60 and 86%, with von der Leyen’s first Commission in 2019 achieving 65%.

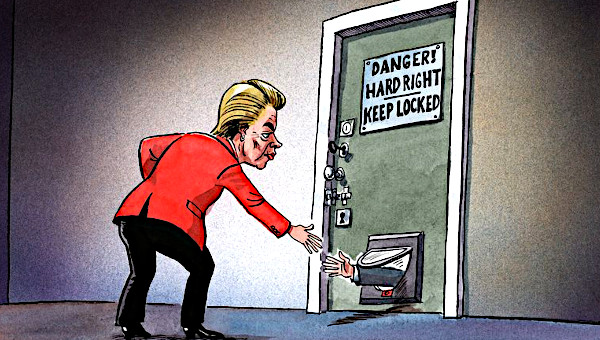

The difference between 2019 and 2024, however, is the strengthened presence of the far right in Parliament (and in society as a whole). Patriots for Europe (PfE), Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN), and the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) together occupy 26% of seats, 8% more than in 2019 and as much as the largest ‘center’ group EPP. They are not peace parties – far from it – some taking extreme pro-Israel positions, but they largely lost in the distribution of the more important positions in the institutions. And if they are generally considered ‘eurosceptics’, it is not out of opposition to neoliberal Europe, but rather out of a backward nationalism coupled with racism and xenophobia. Their opposition to the Platform, the political center, however hard it has shifted to the far right, is a protest for not being included in the power structures, and also a tactic for domestic use, as even a shadow fight against the unpopular EU can be electorally rewarding.

Von der Leyen was well aware of these risks, and used various manoeuvres in order to ward them off. In the past year, a friendship even seemed to be growing between her and Giorgia Meloni, the prime minister of Italy, leader of the neo-fascist Fratelli d’Italia linked to the European Conservatives and Reformists. Von der Leyen was seen joining Meloni in Cairo and Tunis to strike migrant deals with autocratic rulers. And the Commission president attributed as Meloni’s candidate for the European Commission, Raffaele Fitto, has not only a major (multi-billion) cohesion and reform portfolio, but also the rank of ‘executive vice president’ of the Commission.

The social-democratic S&D opposition to the other far-right candidate, Olivér Várhelyi (PfE), sent to Brussels by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban for a second term, also threatened to throw a spanner in the works. The EPP naturally defended the composition of the Commission as proposed by its fellow commission president, including Varhelyi and Fitto. However, S&D’s opposition was met by the EPP’s threat to challenge social democratic Spanish candidate Teresa Ribera, with a key portfolio and the rank of ‘executive vice-president’. Once again, it was the attachment to the Platform that put an end to the bickering, as von der Leyen’s whole edifice threatened to collapse otherwise. S&D was appeased with the transfer of some powers from Várhelyi to the Belgian candidate, the liberal Lahbib. The disgruntled Greens got another treat: their former Green group leader Philippe Lamberts will become an adviser to Madam President. So, finally, the majority of Platform EP groups1 and the right-wing ECR approved the new Commission as proposed by the President.

A Conclusion?

If anything can be concluded from this, it is that we have to reckon with an even more confident Commission presidency than was already the case under the previous one. Von der Leyen has tested how far she can go and found that it is very far. She became Commission president again, notwithstanding that the European Court of Justice condemned her secrecy over vaccine deals with Pfizer. She single-handedly assumed the role of EU foreign policy representative by immediately declaring her support for Netanyahu after the Hamas attack. She made openings to the far-right, though she had said she would not do so. She made deals with autocratic regimes to keep refugees out of the EU, turning a blind eye to the criminal means involved. It was all possible: Parliament found her good for a second term, the Platform of Conservatives, Social Democrats, and Liberals stands firm.

But tackling the real problems is very different from petty political maneuvering. A trade war is looming on the horizon once Donald Trump is installed as US president, the Union is further and further from reaching its climate targets, its Ukraine policy is proving untenable, and it has lost all moral credibility with its migration policy and continuing support of Israel. On the domestic front, the traditional ‘tandem’ of Germany-France is growing further apart. With so many factors at play, it will become clear in time what Platform Europe is capable of. •

Endnotes

- However, not all of them. The Greens were split, the Spanish conservatives (Partido Popular) against, the German Social Democrats abstained. The no vote of the Spanish conservatives was a pure case of their drive for polarization and propaganda at the national level, and out of anger and frustration – because their social democratic compatriot Teresa Ribera finally was given an important portfolio.