Topic: Labor / Economics

-

System Change Not Climate Change

SYSTEM CHANGE NOT CLIMATE CHANGE! The Crucial Demand of Our Time! Degrowing from Chaos to a Steady-State Economy ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS TO CHANGE THE SYSTEM, CHANGE THE MONEY! PARITY ECONOMY JUST TRANSITION MAKE CARBON OUR FRIEND NOT OUR FOE People get it. The realization that we are in the midst of a climate emergency…

-

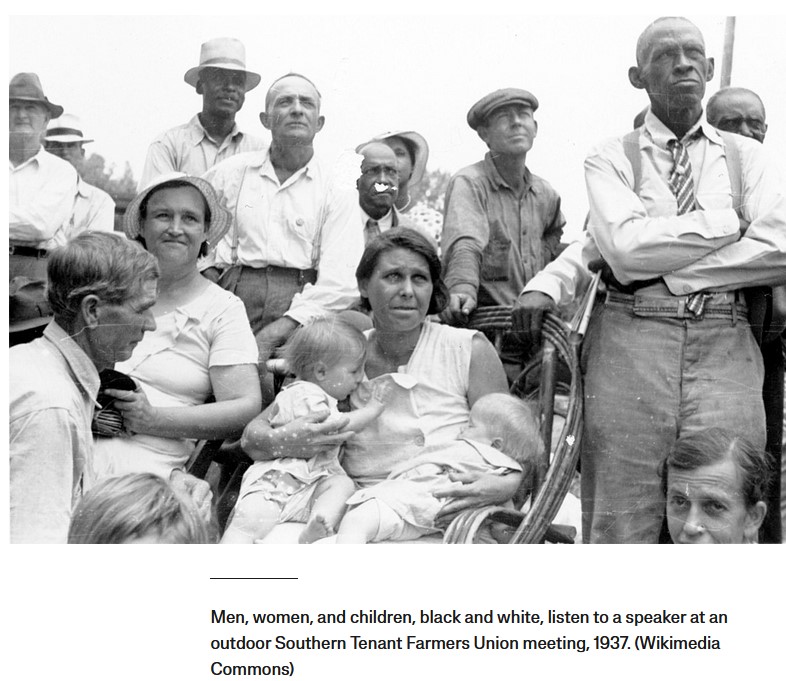

When Black And White Tenant Farmers Joined Together

—

by

The Southern Tenant Farmers Union was founded on the principle of interracial organizing. It challenged the Southern landowning class and the Jim Crow white supremacist order, leaving a proud legacy for both the labor movement and the civil rights movement. It’s 1935 and class war is brewing in Arkansas. Standing before 1,500 black and white…

-

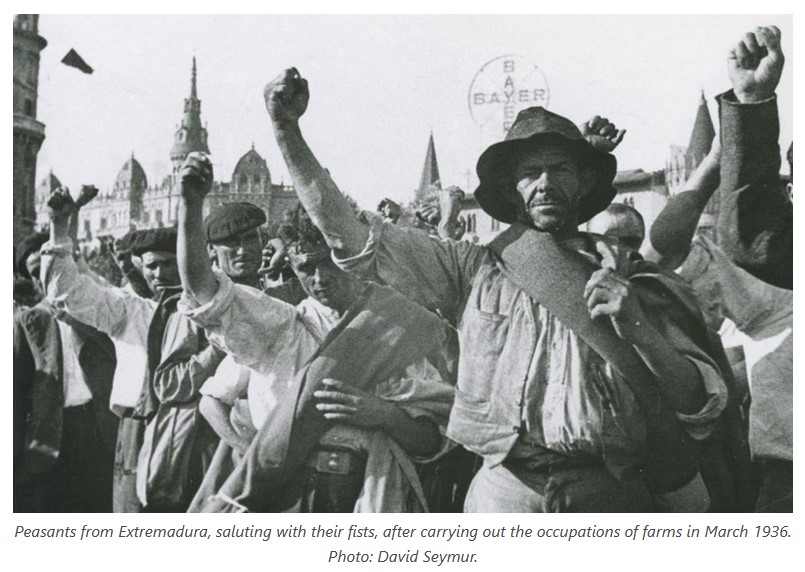

The Spanish Civil War: Lessons In Economic Democracy

—

by

The Spanish Civil War and Revolution of 1936 was arguably the 20th century’s greatest experiment in economic democracy. Spain’s workers and peasants built a new economy in the midst of chaos. Altogether, approximately 18,000 enterprises – nearly all industries in Catalonia and 1700 villages across the country – were collectivized between 1936 and 1937. For…

-

Organizing to Save the World: Building Organizations from the Ground-up

The world is going to hell in a handbasket: war, poverty, inequality, climate change, etc., etc. A look at the day’s headlines or social media flow and that becomes very clear. It’s scary, and it’s very easy to feel overwhelmed and hopeless. You probably don’t know me: I’m an old guy, just turned 72 years…

-

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 5

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 5 —Kim Scipes SUMMARY The preceding four parts have laid out a view that differs vastly from what we are consistently told by our corporate, government, media, and even many of our teachers. You, dear reader, are going to have…

-

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 4

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 4 — Kim Scipes NOTE TO READER: This is the fourth part of a five-part article. It follows the first section on “Neo-liberal Economics,” and is part of explaining essential concepts of this study plus elaborating on how they interact.…

-

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 3

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 3 — Kim Scipes NOTE TO READER: This is the third part of a five-part article. It follows the section on “Globalization,” and is part of explaining essential concepts of this study plus elaborating on how they interact. …

-

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 2

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 2 — Kim Scipes NOTE TO READER: This is the second part of a five-part article. It follows the section on “Imperialism,” and is part of explaining essential concepts of this study plus elaborating on how they interact: GLOBALIZATION[1] …

-

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 1

The United States in the World: Making Sense of the Past Forty Years (1981-2023)-Part 1 –Kim Scipes NOTE TO READER: This is a lengthy article, co-published with Z Network, that is broken up into five parts so as not to make it too overwhelming; the sections differ in length; it will be published on…

-

The Deadly Intersection of Labor Exploitation and Climate Change

—

by

In San Bernardino, California, where retail giant Amazon has a massive warehouse and fulfillment center, daily temperatures reached triple digits for the majority of days in July and have been dangerously hot all summer. Workers with the Inland Empire Amazon Workers United (IEAWU) protested the dangerous conditions and complained to CAL-OSHA, the state’s Division of…