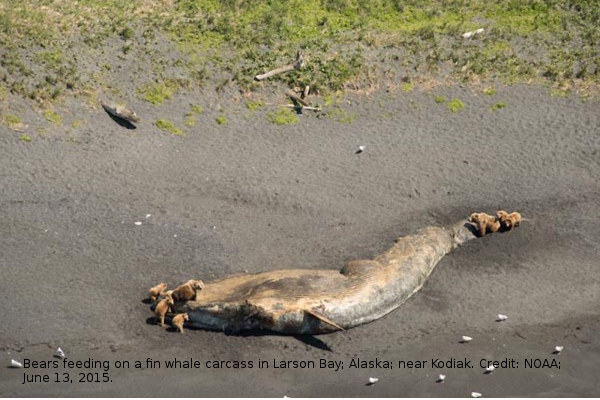

The photo of brown bears feeding on a fin whale carcass near Kodiak is stunning: two species of Alaskan charasmatic megafauna we rarely if ever see together. What's more, there are several bears – a group of mother and cubs at each end of the carcass – because the whale is so large that there is plenty of room for these two parties to feed without bothering each other.

Between May and August, 2015 a total of 11 fin whales, 14 humpback, and one gray whale (and another four unidentified cetaceans) were found dead in the western Gulf of Alaska and along the southern shoreline of the Alaska Peninsula. Although marine mammals are common in the Gulf of Alaska, 30 large whale strandings is about three times the yearly average for this region.

“We rarely see more than one fin whale carcass every couple of years,” said University of Alaska Fairbanks professor Kate Wynne in an interview published by Alaska Dispatch News on June 18, 2015.

Despite the alarming number of floating dead whales, the cause of death has not been determined. Due to the rugged and remote nature of Alaska's coastline, scientists have had limited success obtaining tissue samples from the dead whales (only one washed ashore). Bree Witteveen, a University of Alaska Fairbanks marine mammal specialist working with Wynne on the investigation, noted the one whale carcass they were able to examine had no obvious injuries and appeared to be in good condition.

“It was a really healthy animal; there weren’t any obvious signs of cause of death,” she said.

Laboratory tests for domoic acid, a toxin produced by harmful algal blooms, came back negative for that carcass, but the fact that the whale was badly decomposed when the tissue was collected means these results are not reliable.

When fish feed on the algae and plankton contained in a harmful bloom, the toxin accumulates in their tissues and poisons the marine mammals and birds that feed on them. With sea-surface temperatures in the Gulf of Alaska averaging between 0.9 and 3.6 degrees above normal in 2015, this area was highly susceptible to harmful algal blooms. By summer the widest toxic bloom on record for the west coast reached from California all the way to Alaska.

Toxic algae blooms can also cause paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP). While shellfish are not affected by these toxins, animals that eat shellfish tainted with PSP can become severely ill. Paralytic shellfish toxins and domoic acid are rarely found at the same time in shellfish, but that was different in 2015 too.

THE BLOB

While a harmful algae bloom has not been ruled out in the whale deaths, they may be tied to a larger troubling marine pattern in the North Pacific. The West Coast has seen unusually warm ocean temperatures since 2014, and researchers think these conditions may be the new normal with climate change. A mass of unusually warm surface water, nicknamed “The Blob” by scientists, was about 500 miles long when it was first noticed in 2013 off the coast of Washington. By the summer of 2015 it stretched from Mexico to Alaska.

Teri Rowles, lead marine mammal scientist for NOAA Fisheries says unusually warm conditions both in the water and the atmosphere are worrisome.

“That always concerns us because that means there’s probably a change in overall pathogen exposure, possibly harmful algal blooms and other factors,” Rowles said.

What makes The Blob so dangerous is its effect on the ocean's circulation. Because the warmer water is a dense layer, there is less mixing of nutrient rich colder water from below. When these nutrients don't reach the surface, it impacts the entire ecosystem. Phytoplankton, tiny animals at the base of the oceanic food chain, rely on obtaining nutrients at the ocean's surface where they can get the light they need. As the phytoplankton populations decline in response to this lack of water mixing, the zooplankton and other animals at the next step up the food chain are faced with a shortage of food, which then continues on up to larger fish and marine mammals.

While the warm water blob is wreaking havoc on native marine species, it has also allowed warm water species to move northward. Oceanographers at Oregon State University report that tropical copepods (a type of plankton) are now in the waters of coastal Oregon. Because they are less fatty than the native plankton, predators ignore them, so their population is increasing. At the same time, native plankton began breeding later than usual in 2015 and have seen a population decline.

ZERO BODY FAT

In addition to an alarming number of whale carcasses, the west coast has seen masses of dead seabirds. Beachgoers from California to Canada reported hundreds of Cassin's auklet carcasses during 2014. By January 2015 tens of thousands of the birds had washed ashore, which was 100 times more than reported in an average year. Julia Parrish, a Professor of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences at the University of Washington, says it's possible that the auklets weren't able to dive deep enough to reach their usual prey items, which likely moved to much deeper water to escape the warm water at the ocean's surface.

Then in August 2015 dead and dying sea otters began washing up on beaches in Homer, Alaska. Volunteers for the Alaska Wildlife Response Network have collected over a hundred dead or dying otters on Homer beaches since August, sometimes finding eleven otters in one day. Some of the dead otters appear healthy while others are emaciated. A small sample have tested positive for harmful algae bloom toxins, and some have signs of a bacterial infection that can damage the heart.

In yet another disturbing Alaskan wildlife event, at the end of October 2015, Bird TLC in Anchorage received its first emaciated common murres. Katie Middlebrook, the center’s avian rehabilitation coordinator, reported that necropsies on some of the seabirds revealed “zero body fat.” Through late December murres continued to wander inland, appearing in bizarre places such as the edge of busy roads or in residential driveways. Starving and unable to fly, the birds make no effort to move away when approached. Experts think the murres are wandering inland in a desperate search for food, as they can no longer find the squid, krill and small fish they normally feed on.

Local wildlife rehab centers have been overwhelmed by the number of murres being delivered to their doors, with one center in Anchorage receiving 20 of the birds in a single day. Initially the bird rehabbers planned to send any recovered murres to Seward, Alaska where they would be released into Resurrection Bay, but then dead murres started showing up there as well. With more dead murres appearing at other coastal Alaskan cities, there may be nowhere to return them to.

Though the various marine species seen in the die-offs along the west coast since 2014 (which also includes sea stars, who appear to be succumbing to a virus), are not all dying from the same causes, it seems likely that the underlying cause for all of them is the unusually warm water – the new normal.

CANARY IN THE FISHERIES?

In June elevated toxin levels led to the the largest-ever closure of Washington’s multi-million dollar crab fishery, and the razor clam fishery was also closed statewide in 2015. Fisheries in Oregon and California were also affected. If the warm water trend continues, various fisheries in the Pacific Northwest could be vulnerable to harmful algae blooms and disruptions in the food chain.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologists noted in 2015 that salmon in Bristol Bay and Prince William Sound were smaller than usual, which they attributed to more competition for food in the changing ecosystem. Some fishermen also suspected that sockeye salmon were swimming at lower depths, most likely to find cool water. As drift net depths are regulated, the fishermen were not able to reach these sockeye.

“They claim this year the fish were running deeper,” said Pat Sheilds of the ADFG. “I have no data to show that, but usually drifters know how to catch fish.”

Native villagers in Alaska are also affected. Although toxic algal blooms have always been a concern for them, winter was always considered a safe time to gather shefllfish. Because of climate change and warming conditions, that is no longer true.

Consider this story ongoing. On January 6, 2016 Alaskan wildlife officials announced the finding of an estimated 7800 dead (and extremely) emaciated common murres along just one mile of the shore of Prince William Sound. They are beginning to fear for the entire Alaskan population of this species. That is huge. And if the murres are starving, no doubt other creatures will also suffer.

Then on January 8, 2016 the Alaska Dispatch News reported a ragfish, a species of deep ocean waters, washed ashore in Gustavus, Alaska. These fish are quite large, with the Gustavus carcass measuring 65 inches long. Ragfish, typically found at depths of at least 4000 feet, are rarely seen, although one also washed up near Gustavus in July of 2015. Both of these dead ragfish were females “full of eggs” but with empty digestive tracts. Since little is known about this species, the significance of these two dead individuals appearing within months of each other is hard to evaluate. But it suggests that all is not well far below the unusually warm surface of the North Pacific either.

Sources

https://www.adn.com/article/20150618/9-endangered-whales-found-dead-alaska-waters-recent-weeks

http://www.adn.com/article/20151230/dozens-starving-seabirds-grounded-inland-southcentral-alaska

http://www.alaskafishradio.com/blob-effects-in-alaska-being-watched-by-ocean-observing-team/

http://www.alaskajournal.com/business-and-finance/2015-08-19/warm-gulf-water-algae-bloom-raise-eyebrows-psp-levels#.VobS-Lz_Jz0

http://www.bendbulletin.com/localstate/3747001-153/the-blob-is-no-laughing-matter-for-marine#

http://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov/news/features/west_coast_algal_bloom/index.cfm